Bicycles were associated with wealthy young men in the early part of the 20th century, particularly being favoured by the sahibs and the Indian elite. In a few years, as bicycles became more common and popular, the prestige waned. By the 1920s it was not seemly for a senior official of the Raj to gallivant about on a cycle. A horse or carriage was seen as a better way to maintain distance and underline class distinctions. It was also not deemed acceptable to turn up to work or elsewhere looking hot and bothered due to cycling in the tropical weather. By then motorcars were making an entry as well so bicycles were bumped down the hierarchy to be the vehicle of choice for junior officials and the natives.

Today cycles continue to be the ambit of those lower down on the socio-economic hierarchy. A survey of 480 of these livelihood or captive cyclists in Chennai, conducted by CAG, found that the majority of cyclists are men (no surprise there!) and over 75% of the cyclists earn less than Rs 20,000 per month. We interviewed 147 women cyclists, 324 men, and 10 people who did not identify with either gender. The savings on transport on a daily basis was a clear reason why many cycled - around half the respondents said this was an important consideration when it came to their mobility choice. The other top reasons why they chose to cycle was convenience (318 respondents - some chose multiple reasons), and because it saves time (318). Many of them had jobs that required several trips around the city in the day and so cycling made more sense in terms of time and money compared to public transport or a two-wheeler.

Image: Mixed traffic situations are unsafe for cyclists

The invisibility of cyclists

While cyclists are a dying breed on Indian roads (literally and figuratively), a few continue to cling on tenaciously. The traffic being what it is, we asked these intrepid cyclists what were the issues they faced on the road. According to 278 respondents (nearly 60%) the main issue is drivers of other motor vehicles and their behaviour. Cars, two-wheelers, buses, vans etc often speed past without giving any space for the cyclist. When they pass with inches to spare, it is nerve-wracking for the cyclist. This is something that even those of us who have never or rarely cycled, experience. Most of us must have experienced walking down a road, and having a two-wheeler zip past, almost touching us. That always leaves us feeling a little shaken and annoyed that the driver didn’t have the sense to leave a little space. Cyclists face this multiple times a day. Another complaint was that motor vehicles tend to suddenly slow down after cutting in front of a cyclist, sometimes they turn without signalling so the cyclist has to halt. The constant honking was another irritant for cyclists.

Other than motorists’ behaviour the major challenges cyclists faced were poor road surface (34%), lack of cycling infrastructure (14%), and the proliferation of flyovers (13%). While the poor road surface is something that all road users face, the other two challenges were interesting. The cyclists were clear that an allocated lane for cyclists is important in reducing the general lack of safety they feel on the roads. Some of them mentioned that they had seen the cycle lane markings in some stretches but it made no real world difference to their safety. This is unsurprising as the lanes they are talking about is literally just a line painted on the road. Cities that truly want to support cycling, must make dedicated cycling tracks which are well-segregated from motor vehicles. In many countries, this separation is done by the pavement/footpath, that is the cycle lane is on the left lane, followed by the raised pavement and then comes the space for motor vehicles.

The issue of flyovers shows how planners are clearly building these mountains of concrete for motor vehicles and not for the lowly cycle. Rarely do you see a cyclist attempting to cycle up a flyover. As a corollary, flyovers reduce space for cyclists as the road space below the flyover is narrow and is used by buses (which also find flyovers unsafe to navigate) and other motor vehicles. Interestingly, there was no real difference between men and women when it came to what problems/issues they faced on the road.

Mind maps and route plans

We also asked cyclists what kind of roads they preferred. Were they happy to pedal along main roads or tried to avoid those and hug smaller residential roads which had less traffic, more trees, etc?

Fig 1: The road taken: road preference among livelihood cyclists in Chennai

Of the 147 women, 100 of them (two-thirds) expressed a clear preference for smaller, quieter roads. Only 28 women said they had no issues with main arterial roads and another 19 said they had no preference between the two and used both small, local roads as well as main roads. While men too, by and large, preferred smaller roads, in terms of percentage it was just over 50% (171 men out of 324) who expressed this preference. A little under one-third (98/324) of the men were happy with main roads, and about one-sixth (55/324) were comfortable with both kinds of road.

So while lack of safety (due to poor driving by motorists) was an universal issue, it looks like women prefer to reduce their risk of a road incident by avoiding heavy traffic on main roads. Men were more ready or perhaps had greater confidence in their ability to safely navigate traffic and hence were quite happy to use main roads. It could also be that with men typically cycling for longer periods of time (i.e years of experience), their confidence in navigating heavier traffic was greater.

Most of the cyclist deaths in India are of men according to the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRTH) and the top 5 vehicles that kill cyclists are cars (1241 deaths in 2021), two-wheelers (1210), trucks (933), buses (315), and auto rickshaws (264). Perhaps, the risk reduction strategy of women cyclists is paying off. MoRTH, in its report, Road Accidents in India 2021, notes that in 2021 the number of cyclists killed in India was 4702. This was a substantial increase from the previous two years: 4196 in 2019 and 4167 in 2020. It is interesting that in spite of lockdowns, the deaths in 2020 did not decrease substantially.

Cyclists are 3% of fatalities on Indian roads. With increasing motorisation, increased speeds, and single-minded focus of planning authorities on making the roads only about motor vehicles, these numbers are only set to increase.

Several cyclists also highlighted that bicycle theft is a concern. This was linked to lack of safe parking in public spaces such as commercial areas. Cyclists end up parking on pavements, thus adding to the obstructions faced by pedestrians, or they park on the carriageway among two-wheelers. Under these circumstances, there is a high risk of theft. For livelihood cyclists this is a big blow as the cycle is their main mode of transportation. And while new bicycles do not cost as much as a two-wheeler, such an expenditure can still dent the family’s savings.

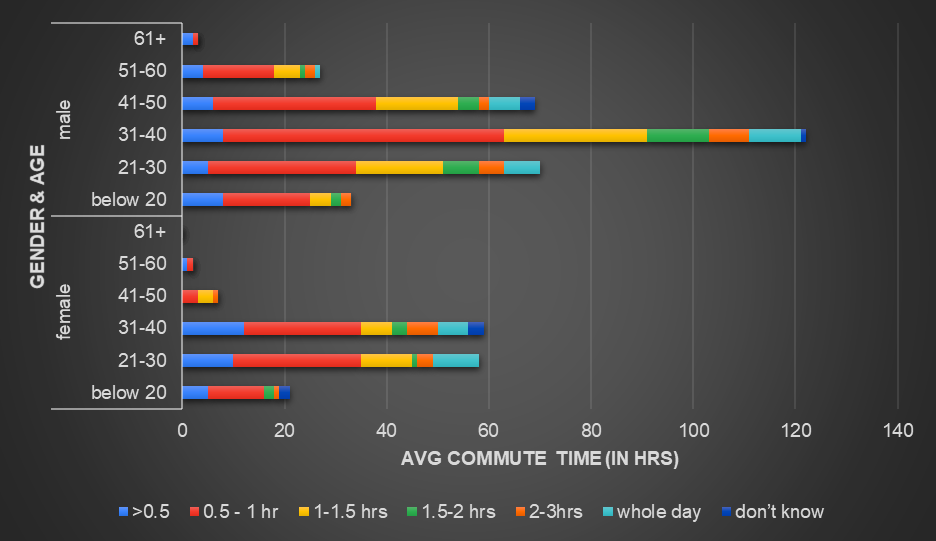

Fig 2: Are we there yet?: Average daily commute time of livelihood cyclists in Chennai

We had also asked cyclists what their average daily commute time was. Most people were cycling for an hour or less in total which translates to a maximum of 15 kms per day. Except for students and the elderly, there were also, across age groups, a few people who cycled the ‘whole day’ which means they did multiple trips throughout the day and they were not necessarily the same daily.

The commute patterns, safety concerns expressed, the number of deaths recorded all call for planning and development of good cycling infrastructure - curb-side parking, cycle lanes, and priority for cyclists at intersections. Cycle lanes do not have to be on all roads. As indicated by the cyclists interviewed, smaller, residential roads are relatively safer and do not need intervention but arterial roads need to be planned and designed with cyclists in mind. Smaller roads could, where needed, have speed calming measures introduced.

For the nearly 50% of cyclists who cycle for more than an hour daily, ensuring parking at stations/bus depots and allowing cycles on board suburban trains and metro could ease the commute difficulties and make for safer and more comfortable travel. Recently, in Bengaluru, buses with a cycle rack in the front were introduced. This could be another great option for bus routes that cover long distances cutting across the city. Such conveniences and interlinks with public transport would encourage more people to shift modes to a combination of walk/cycle/public transit.

An uphill task ahead

The study gave us an inkling of what it means to cycle in today’s Chennai and the Sisyphean task ahead in ensuring safe mobility for cyclists, thereby creating an ecosystem that encourages a modal shift to sustainable mobility choices in the city. With the recent publication of the Chennai Climate Action Plan, such nudges will be crucial in achieving the ambitious goal set of having 80% of trips in the city by walk/cycle/public transit by 2050.

Add new comment