It is a truth, universally acknowledged, that our cities are pedestrian-unfriendly. For years, Indian cities have widened roads at the expense of footpaths, pushed pedestrians towards foot overbridges and subways so that they don’t get in the way of vehicles. The focus of traffic planning and mobility has been to prioritise motorised traffic as if motorised transport is superior to other modes.

At the same time, globally there has been a growing recognition that motorised transport is not sustainable. European cities are switching to promoting walking, cycling, and public transport for this very reason. In India, many are talking the talk, but implementation has been slow, in fits and starts. There have been policies, missions, and plans but somehow they all seem to function in silos. Take Chennai for example. It has the distinction of being the first Indian city to adopt a Non Motorised Transport (NMT) Policy in 2014, with some excellent goals of making the city roads walkable, with cycle paths such that transit modes would switch strongly back to NMT and public transport and thus reduce congestion, pollution, and make the city more liveable and sustainable.

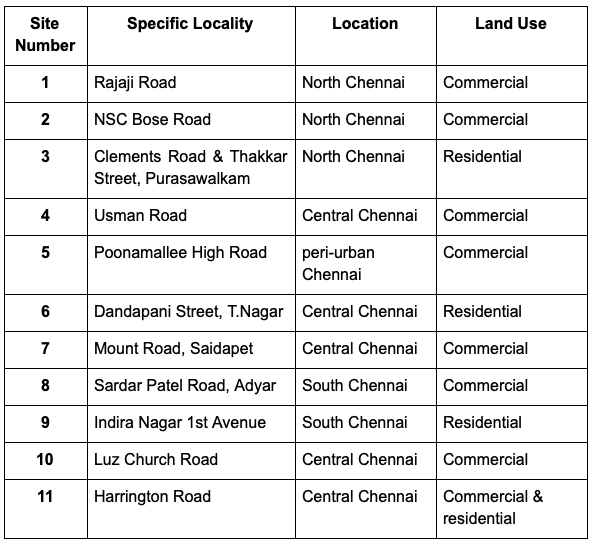

It's been 5 years since, and CAG decided to assess if the city is safer for pedestrians. We looked at nine locations across the city covering commercial and residential roads. In addition, two more locations were assessed which were chosen because a pedestrian-focussed redesign had been carried out there. The idea here was to see how such a redesign had fared. At each site, pedestrian infrastructure was assessed for a one kilometre stretch of road by measuring the width and continuity of footpath, surface quality, extent of encroachment, walkability of footpath, and accessibility. Foot overbridges and subways were also assessed in terms of accessibility, safety, and cleanliness. Pedestrian crossings were assessed in terms of safety and ease of use (duration of timed lights, was the crossing clearly marked, were there median refuges, etc). CAG’s study was published in the Journal of Road Safety and can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.33492/JRS-D-20-00249

The NMT Policy has as one of its goals, changing the mindset of road users towards NMT and making NMT usage aspirational. This would then require people to stop looking down at pedestrians and cyclists and stop wanting to swat them away like pesky flies. To get a sense of whether there had been a mindset shift, we carried out a perception survey with 37 road users (covering gender, age groups, and type of vehicle being driven). The road users surveyed were eight auto rickshaw drivers, seven car drivers, seven two-wheeler riders, four bus drivers, and 11 pedestrians. The bus and auto rickshaw drivers were all men since women in these categories are rare. We asked if they thought pedestrians were safe, whether pedestrians had any rights on the road and what needed to be done to change existing perception.

Table 1: 11 locations chosen for the survey

The last 2 roads have been redesigned a few years ago by the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) to be more pedestrian-friendly - wider, evenly-laid footpath, bollards to prevent motor vehicles getting on the footpaths, median refuges for safer crossing, clearly marked pedestrian crossings and so on.

What did we find?

In Rajaji Road (near Beach Station), the footpath was walkable (evenly laid tiles, footpath wide enough for two walk abreast, no obstructions) for about 50% of the surveyed area. Our findings were similar in Mount Road (near Little Mount metro station and the Saidapet bridge), Luz Church Road, Harrington Road, and Indira Nagar First Avenue. However, none of these locations were free of problems - all of them had encroachments - shops, roadside vendors, parked vehicles, and garbage. Similarly, none of the sites were access-friendly; roads that had ramps to access the footpath also had inappropriately-placed bollards making footpaths inaccessible for wheelchairs.

Rajaji Road had narrow footpaths (just enough for one person) for most of the distance surveyed with only short stretches being wide enough for two people to walk abreast. On the eastern side, i.e. along Beach Station, the footpath was narrow, just enough for one person to traverse it. This stretch has a row of small shops that have encroached upon the footpath and so pedestrians have to skirt their customers who have no place to stand but the footpath. Thanks to the narrow footpath and the many two-wheelers parked on the road, pedestrians heading to and from Beach station just find it easier to walk on the road. The western side of the road was marginally better with short stretches of 100m having slightly wider footpaths but these too were occupied by roadside vendors, bus stops, and the subway entrance, leaving little space for the pedestrian.

Image 1: Shops encroaching upon footpath, Rajaji Road

In the commercial areas of NSC Bose Road, Usman Road, and Sardar Patel Road (in Adyar) less than 50% of the road had a footpath wide enough for two people to walk abreast. Unfortunately they made up for it by having uneven, broken tiles on the footpath and of course the ever present encroachments.

In the residential roads in Purasawalkam, T. Nagar, and Indira Nagar First Avenue, only Indira Nagar had contiguous, and neatly laid footpaths but there was no getting away from the encroachments! In Indira Nagar, the road is blessed with some lovely trees but is not well lit. This, of course, makes pedestrians all the more reluctant to walk on the footpath where one might step on God-only-knows-what!

In Harrington Road, the footpath was wide and in good repair albeit with a little encroachment by shops and utilities. Harrington Road had wide footpaths on either side, evenly laid, with bollards to prevent vehicles from driving on them. There is a clearly marked at-grade pedestrian crossing with median refuge and curb extensions.

In Luz Church Road, for a short distance (about 600 m), the footpath is about 3m wide and has clearly been designed with the pedestrian in mind. However, the footpath width abruptly changes from 3m width to about 1m wide after this stretch. Throughout, be it in the wider or narrower sections, the footpath is encroached by shops, vendors, temples, parked vehicles, and garbage.

Image 2: Redesigned footpath in Luz Church Road encroached upon

Cross the road at your peril!

In terms of facilities for pedestrians to cross the road, most sites did not have any. In one site, Mount Road, there is an at grade crossing with a pedestrian light and a foot overbridge right next to each other. Obviously pedestrians did not use the foot overbridge and preferred to wait for the pedestrian light to turn green to cross the road. This section (near the Saidapet Court) being an one-way and traffic being relentless even if the pedestrian light is green, makes crossing the road quite scary. The pedestrian light is only for 30 seconds which is inadequate for such a wide road which does not have a median refuge either. Even the young and able have to hustle to cross the road in 30 seconds.

In Rajaji Road there was one subway and one at-grade pedestrian crossing with a 10 second pedestrian light. The duration of the light was inadequate for pedestrians to cross the road; they were only able to cross halfway. The subway was in good repair and it was observed to have heavy patronage by people accessing the adjacent suburban railway station. Yet many people preferred to risk life and limb to clamber over the central median instead of walking down to the subway.

The worst of the surveyed locations was Poonamallee in peri-urban Chennai. It had no pedestrian infrastructure - no footpaths, no pedestrian crossing though the road is a highway and a busy local bus stand is situated there!

Pedestrian Perception Survey

Almost all motorists interviewed admit pedestrians have rights but for many it was limited to footpaths and crossing at pedestrian crossings. Some motorists felt that in many roads, footpaths are being constructed so pedestrians should be fine. The main problem cited was that pedestrians insist on walking on the road.

Pedestrians, of course, were clear that walking in Chennai is hazardous to health – motor vehicles give scant regard to them; footpaths are non-existent; and crossing roads is difficult as vehicles do not slow down even at pedestrian crossings. In addition, pedestrians noted that motorists drive haphazardly making the pedestrian experience more traumatic. Pedestrians were emphatic that they did not feel safe on the city’s roads and two major changes were required - one was the quality of footpaths, and the second was recognition of pedestrians as a legitimate road user by motorised vehicles.

So what then?

There has been no doubt as to what kind of city we need and what we need to do to achieve. The problem continues to be in converting the ideas into reality. We need pedestrian, cycling, and public transit infrastructure to improve tremendously. We need simple, functional infrastructure that works for everyone irrespective of age, gender, socio-economic background, physical ability, and language knowledge. In addition, we need a mass rewiring of our brains - and this is going to be the tough part - to understand that everyone has a right to the road.

To achieve this, we need the government to discourage private transport and incentivise public transit and NMT. The GCC must come down hard on encroachers - especially the big ones - and make arrangements for small vendors to ensure their livelihood is not affected. GCC has announced many projects - Smart Cities, Chennai Mega Streets and so on but all of these are piecemeal. Coming down on big encroachers, making public parking very expensive and in general making, owning and using private vehicles a burden are not popular politically but this is what is needed.

We could do with a dose of tough love.