In 2015,the Modi government announced that 100 cities had been shortlisted to compete for funds under a new urban development initiative called the Smart Cities Mission. Since then, 20 cities, including Chennai, have won the first round of funds based on their proposals for smart projects in their city. The idea of a smart city is a global idea with no universally accepted definition. How each country or city chooses to define a smart city varies depending on a range of factors including level of development, resources, and aspirations of the city’s residents. In India, the government lays out the objective of the Smart Cities Mission (SCM) to promote cities that provide core infrastructure and a decent quality of life to their citizens as well as a clean and sustainable environment and the application of smart solutions. While this idea sounds great, a few key issues stand out when looking at the Smart City guidelines and proposals for the scheme.

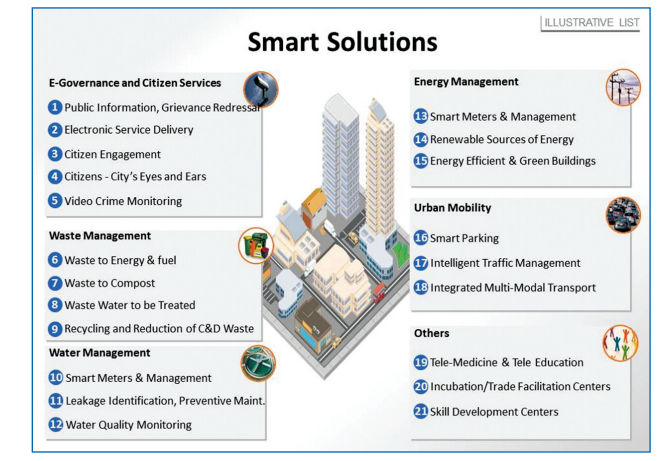

Figure 1: Smart Solutions (Source: Government of India)

First, the opportunity for private interest to take over is extremely high. Smart cities projects will be implemented by an autonomous Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), created specifically for each city, which will be headed by a CEO. Unlike the government, the SPVs are not democratically elected. SPVs will be authorized to “plan, appraise, approve, and release funds” as well as manage, operate, and monitor the Smart City projects. They will also be given authority to collect user fees and taxes. The mission also strongly suggests using public- private partnerships (PPPs) and joint ventures to help finance projects. Such a highly autonomous implementing vehicle as well the as reliance on PPPs for funding raises concerns about the power of the government to protect the rights of citizens as well as about the motivations that drive decisions and how inclusive those decisions will be. Another key concern is the ability of citizens to hold the SPV to account should they have an issue with the project.

Second, each city is asked to submit an area based plan, focused on redeveloping or developing one area of the city, and a broad city-wide plan. The SCM focus on area- based development for the city risks excluding large sections of the city, as only small enclaves will reap the majority of the benefits of the Smart Cities Mission. It also risks replicating or perpetuating practices of spatial segregation where attention is paid to middle and upper-class areas leaving out areas in the greatest need. The smart city guidelines do highlight affordable housing “especially for the poor” as one of the key infrastructure elements. However, what is considered affordable and to who is not specified. Similarly, there are no provisions to protect the affordability of the housing or other services as the area becomes more desirable to live in. Finally, if the government continues to provide land and housing for the poor in undesirable areas, as it has done, it will only continue to contribute to the segregation of wealthier, well-serviced areas and those where the poor can afford to live.

Third, smart city proposals are judged in part on their engagement with citizens, but what this engagement should look like according to the government is vague. The World Bank notes that engaging various actors in participatory decision-making is an important way of reaching a balance between different levels of power, creating a platform for actors to communicate on an equitable basis and address problems and set priorities. Making new spaces for citizen participation allows for differing opinions to come to light and enables people to speak on issues that were previously denied to them. However, public participation does not inherently equate to empowering citizens with the ability to influence change. Therefore, it is important not only to have citizen engagement but also to consider what that engagement looks like. According to the Smart City Mission guidelines, citizen engagement plays a key role. The guidelines state that “the proposal will be citizen – driven from the beginning” and achieved through citizen consultations. During these consultations, the “issues, needs and priorities of citizens and groups of people will be identified and citizen-driven solutions generated.” However, the guidelines do not specify how consultations should take place or create any benchmarks for evaluation. This leaves a large amount of room for interpretation by each city. Similarly, when looking at smart city proposals the variation in how much information on citizen consultations was included was significant. In the case of Chennai, the annex describing citizen engagement was for another city entirely! This variation and ambiguity in guidelines make it extremely challenging to monitor the actual involvement of citizens in the process of creating smart cities projects, who is allowed to be involved, and to what degree this involvement results in the ability to influence change.

Over the next few weeks, this blog will further explore different approaches to citizen engagement as well as how to evaluate aspects of transparency and accountability in the smart cities projects. It will also look in depth at proposed projects in the Chennai neighborhood of T. Nagar and in Ponneri. It will explore the proposed changes for those areas and look at how they contrast with the current uses of the area. Additionally, it will attempt to highlight the ways in which the projects will impact the lives of people living in the area currently.

Add new comment