What is it about buses that brings a wave of nostalgia over most of us? I still remember the bus numbers of routes I used to frequent decades ago, and my heart skips a beat when I come across them on the road today. I remember taking the bus alone for the first time in Madras (now Chennai) when I was ten. My father gave me his visiting card to show a grown-up in case I got lost, but my older brother had little faith in this plan and surreptitiously followed my bus on his cycle. I haven’t forgotten the mixture of annoyance and relief when I saw him pedalling furiously behind my bus. Ever since that day, I took buses everywhere – crisscrossing the city in them, to school, visiting family and friends, or to the movies. Some bus conductors became old familiars, peering at my record books and project charts, offering gentle advice and taking genuine interest in my work. They offered up their seats to school kids studying for a test. They often slowed down if they saw us running to make our connection - the PTC buses of yore were the default mode of transport for many Madras residents and bring to mind a gentler time.

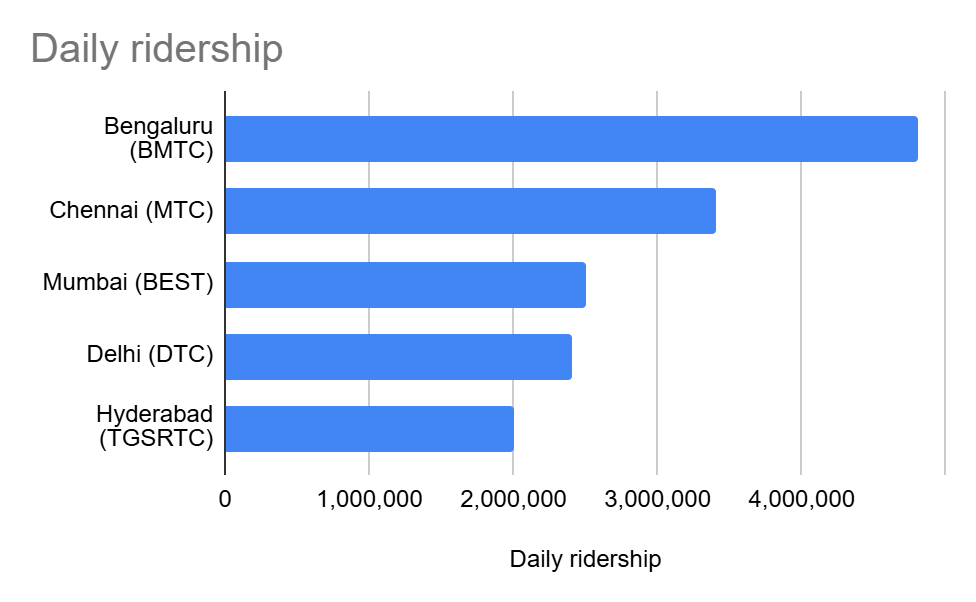

Why the past tense, you may ask? How have I, along with many others, transitioned from buses to ride-hailing apps? Let’s first look at how many people still take the bus in Chennai. From a ridership of 5.5 million in 2010, numbers have fallen steeply—by nearly 60%—to about 3.3 million today. This makes me sad because today we live in a world where the word sustainable has almost become a catch phrase. Yet in the years before we’d even started thinking about sustainability, we were actively making those choices. (Of course, some might argue that we didn’t really have other options.) Before Madras became Chennai, way back in the 70s, 95% of all trips were sustainable with buses alone at 42%. Fast forward to 2018 - sustainable travel had dropped to 55 per cent in Chennai, with buses at 22 per cent.

Is this because people no longer want to take the bus? Not at all. The real issue is that the city’s transport system has struggled to keep up with growing demand and urban sprawl.

What plagues our bus services?

Chennai’s Metropolitan Transport Corporation’s (MTC) fleet now meets only about half the city’s requirement, leading to long waits and overcrowded buses. For many commuters, especially those living in newly developed or poorly connected areas, routes are either circuitous or infrequent, making daily travel inconvenient. Poor first- and last-mile connectivity, unsafe or incomplete footpaths, lack of shaded waiting areas, and limited feeder options discourage people from using buses regularly. Safety concerns, particularly among women, add another layer to the problem. “Women-only” buses offer some relief but do not fully address the issue—long waits at isolated stops and overcrowded conditions make bus travel feel unsafe or uncomfortable. Jenny Mariadhas from Poovulangin Nambargal is currently working on a study that seeks to understand why women avoid traveling by buses - groping, lewd remarks are just the tip of the iceberg. She adds that drivers and conductors must treat commuters with respect and be trained to handle unruly behaviour promptly and sensitively and clear penalties apply to anyone who disturbs or harasses others on board. But even with these measures in place, it remains true that our bus frequency is woefully inadequate, and only this will ultimately decide how well patronised the services are.

Our buses are designed to carry about 69 passengers (including those standing), yet it is common to see well over 100 people packed inside. As a result, many people have turned to two-wheelers, cars, or app-based transport for greater flexibility and a sense of security. Together, these issues have eroded confidence in what was once Chennai’s most dependable and democratic mode of public transport.

Bus Users Speak Up

This is not just true of Chennai. A 46-city study on public transport shows that bus users and even drivers and conductors are a disgruntled lot. Among commuters, 64% cited long waits and unreliable service, while 68% reported severe overcrowding. Drivers and conductors face similar pressures; nearly half say traffic congestion prevents them from meeting schedules, and many suffer health issues without adequate insurance or healthcare. 27% of passengers find it difficult to find a bus stop! Clearly, this system is broken and needs an urgent rehaul.

Despite all these problems, 23.8% of Chennai’s residents still use shared or public transport while 26.5% of Chennai’s residents walk or cycle. Only 44.2% rely on cars. If over half the city already travels sustainably even in such poor conditions, how can we build for them and encourage more people to return to the bus?

Although bus ridership seems to have reduced, a sizable number still take the bus | Source

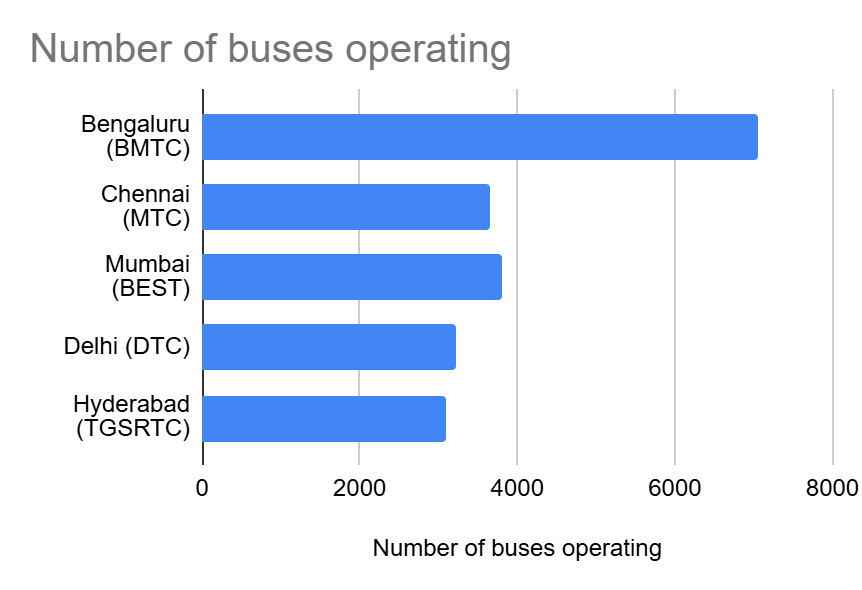

The first step is simple: we need more buses on the roads. Although Chennai ranks second in India in terms of number of buses per 100000 people, it is still only 30-35 buses per lakh - even this is below the 60 buses recommended by the government. Compare this with London which has a lower population but runs more than 100 buses per lakh.

We simply do not have enough buses. Graph above shows the number of buses in top-tier cities | Source

We also need buses that are comfortable, frequent, and accessible. If every bus were air-conditioned, low-floored, and well-connected, ridership would not just recover; it would thrive once again. While the good news is that Chennai will be rolling out 625 electric buses by the end of this year and another 600 buses next year, we will still not be able to keep up with the demand unless the minimum number of buses is met.

Buses vs Metros? No Competition!

You may think that it’s not worth investing in more buses when vehicle ownership has gone up in most Indian cities and metros are being constructed as well. But there is still a very strong case for buses. Firstly, buses are an accessible and equitable form of transport – they serve everyone; rich, poor, old or young. They are efficient – and use less space on the roads, reduce congestion and are cheaper to expand than the metros. They are flexible – it is easier to change bus routes according to demand or on special days while metro routes remain rigid. It’s also easier to hop on and off a bus rather than enter a metro, go through security, scan the ticket, climb up or down to the platform – exhausting just thinking about it! I’m not dissing metros – no I love them! But buses have a special place in transporting people within a city that a metro cannot compete with.

“But I would rather take my 2-wheeler or car than be stuck in traffic while on a bus,” you might say. Agreed. Nothing is more frustrating for a bus user than to be stuck in a jam – why are sustainable commuters punished for making a good choice? We did try to solve this problem with the BRTS , implemented in 11 cities at huge costs and now being dismantled one by one! The reason? It was a case of the cart running before the horse – a BRTS needs buses on the lanes constantly ferrying passengers – instead what we saw was cars stuck in congested lanes while the BRTS remained empty with hardly any buses on them. The promised fleet sizes, low frequencies and operational needs like junctions and pedestrian crossings were not delivered. People found themselves in even more congested non-BRTS lanes that had many safety issues and protested vociferously against this system. Even in cities like Ahmedabad, where it was seen as somewhat successful, certain stretches merged with other traffic. Sundaram R Iyer remembers a time when Chennai attempted segregated lanes. "I think it was in the late 90’s or early 2000s when we had segregated lanes for buses and 2-wheelers for a few months along Mount Road. I remember enjoying driving during that time. There was less stress and less chances of unpredictable movement of vehicles. Unfortunately pushback from certain quarters put an end to this progressive idea."

Solutions are not rocket science

What then needs to be done to rescue our beleaguered bus services? Double the fleet size or triple it in some cities and increase service frequency. Create dedicated bus lanes that move buses efficiently through traffic. Prioritise last mile connectivity where people can walk on shaded footpaths. Ensure that buses are accessible and wheelchair compatible - train drivers and conductors to help commuters with challenges. Make buses more comfortable for commuters with air-conditioning ( sadly this is essential and not a luxury as temperatures rise every year.) And last but most critical, make buses and bus stops safe for women with lighting and even CCTV cameras if needed.

This is exactly what Double The Bus, a nation-wide initiative run by sustainable mobility organisations and civil groups is asking for. The campaign kicked off in September with over 12 cities participating with great enthusiasm. “The reason Double The Bus resonated with so many citizen groups across India is because it’s a basic, reasonable demand like asking for clean drinking water. Comfortable and reliable buses, a norm in most developed cities, shouldn’t feel like a utopian dream here,” says Brikesh Singh, Chief of Communications, ASAR and Coordinator for Double The Bus.

Double the Bus initiative kicks off in Chennai

India is waking up to the paucity of buses. The CM of Delhi has promised to double the number of buses in a year’s time. In Maharashtra, Mumbai plans to increase its fleet of e-buses from 711 to a whopping 8000 by 2027 and Nagpur seeks to expand its fleet as well. Increasing the number of buses isn’t just about transport reform; it’s about equity and climate resilience. For commuters, buses are a low-cost and hassle-free way to move around the city. In the face of climate change, investing in more buses is a simple, powerful step that will build a more sustainable city. And perhaps then, we can all once again be confident in taking the bus as a safe and reliable way of moving through the city.

Add new comment