The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) ‘Housing for all’ programme was launched by the current Prime Minister of India in June 2015. As the name suggests, the programme envisages to provide affordable housing for the poor in urban areas. It falls under the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation and is chaired by Mr. Venkiah Naidu. PMAY proposes to build 2 crore houses for the urban poor and economically weaker sections (EWS) of the society. The programme, though very optimistic on paper, is merely a redecoration and change in the title of an already existing programme, Rajiv Awas Yojana (2009), which was launched by the previous government (United Progressive Alliance or UPA), and was also a centrally proposed scheme set up to make India ‘Slum-free’ by 2022.

Prior to these programmes, the UPA government had also announced the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) in 2005 as a mission to improve infrastructure and standard of life in cities. Basic Services to Urban Poor (BSUP) and Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme (IHSDP) were two programmes under JNNURM. It is no surprise if one tends to get lost in all these ‘yojanas’ and schemes adopted by the government. The crux of the matter that needs to be understood is if these schemes are implemented to the extent they are projected to do so or are they merely political stunts adopted by parties to lure votes from the weaker sections giving them an idealistic vision. To better understand this, a critical evaluation and review of these policies in a chronological order is required.

Basic Services to Urban Poor (BSUP) and Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme (IHSDP) were two sub-missions under the JNNURM (2005). BSUP focused on providing services like water supply, toilets, waste water drainage, solid waste management, p power, roads, transport and access to legal and affordable housing for urban poor. IHSDP, on the other hand, focused on creating a more inclusive approach to urban planning and city management. The objective was to ensure land was available to the poor at affordable prices through the reservation of land for Economically Weaker Section housing and ensuring facilities for urban infrastructure, and transport services on the fringes of the cities, can provide alternatives that would restrict the formation of new slums. Under BSUP and IHSDP component housing units are provided to urban poor. As per GOI guideline beneficiary contribution could be around 12% of project cost for general category and 10% for urban poor belonging to Special Category.[1]

According to data published by Graham Norton, the total projects that were approved under BSUP were 213, with a total approved cost of INR 17,503 crore. The release (as of 2011) for the sample cities were INR 5,836 crores which is merely around 33% of the total approved cost. Of these 213 approved projects, a mere five projects have been completed. The total expenditure (as of 2011) has been worth INR 4,280 crores which constitute around 24% of the approved cost and 73% of the total release till date. To quote the report, “In Chennai, the funds are released only after Third Party Inspection and Monitoring Agency (TIPMA) reports are forwarded to and approved by the CSMC. When the reports are delayed, the funds are consequently delayed.”

The projects get delayed due to this and the beneficiaries tend to lose faith in these projects and develop a strong resistance to relocation/development. Moreover, with the launch of Rajiv Awas Yojana, it was largely ambiguous to how BSUP and RAY were to be integrated by the state governments. Lack of suitable guidelines and delegation from the central government were reasons for the underwhelming results of the two relatively analogous policies. Under the report’s appraisal not even a single sanctioned project has been successfully completed under IHSDP scheme, while the BSUP component also has a low level of completion of 2%.

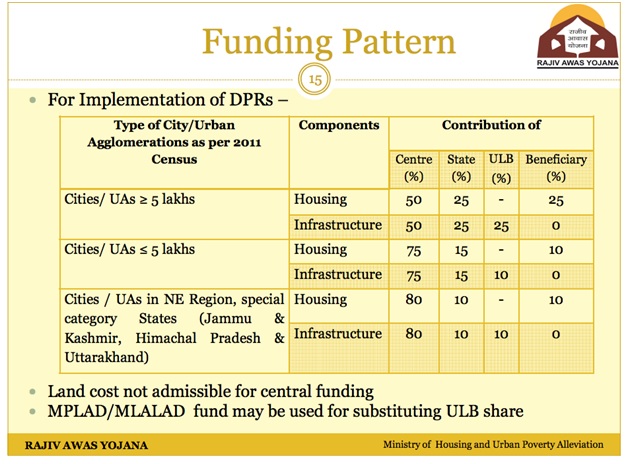

The Rajiv Awas Yojana was announced by the President in 2009.[1] However, it took over two years to formally launch the programme, and another 2 years to transit to the implementation phase. RAY in the vision for a “Slum free India” proposes a two-step implementation strategy: 1) Preparation of Slum Free City Plan of Action (SFCPoA) and 2) Preparation of projects for selected slum. The implementation of RAY is divided into three levels, Central, State and City with respective authorities appointed to supervise it. Under RAY, The Central government provides an assistance of 50% of the project cost for Cities/ UAs with Population more than 5 lakhs, 75% for Cities/ UAs having population less than 5 lakh. There exist certain exceptions on the North-Eastern Region and special category States (Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh & Uttarakhand) where central share was an equivalent of 80%. There is an upper ceiling of INR 5 lakh per dwelling unit (DU) for cities with population more than 5 lakhs and INR 4 lakhs per DU for smaller cities with population less than 5 lakhs. In North East (NE) and special category States, upper ceiling is INR 5 lakhs per DU irrespective of population of the city.

For the approval of projects, Detailed Project Reports (DPR) are submitted to the Ministry after the approval of State Level Sanctioning Committee. The DPRs are then appraised by the Central Sanctioning and Monitoring Committee (CSMC) after which a decision is taken with regard to the approval/sanctioning. The RAY was however remodeled and re-launched under the new name of Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana by the current Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana’s inception and supersession of RAY can be attributed to the change in the ruling party (from United Progressive Alliance to National Democratic Alliance in 2014), The PMAY in comparison to RAY though adopting quite a different approach in the issue of ‘Housing for All’ is quite similar in its objective of achieving ‘Slum free cities’ by 2022. PMAY in contrast to RAY is much more decentralised in financing the construction and development of the dwellings. RAY on the other hand involved a larger role by the centre. Nearly 75% of the project costs were to be borne by the centre and the remaining by the State government and a minimal amount by the beneficiaries.

The PMAY aims to provide assistance to Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) and other implementing agencies through States/UTs for:[1]

- In-situ Rehabilitation of existing slum dwellers using land as a resource through private participation

- Credit Linked Subsidy

- Affordable Housing in Partnership

- Subsidy for Survey-led individual house construction/enhancement

In-situ Rehabilitation through private participation

Under this vertical land is used as a resource with private participation whereby private developers provide housing along with basic civic infrastructure to the eligible slum dwellers and in return they are given a “free sale component” which can be sold to the open market by the developers. As stated in section 4.8.9 of the PMAY ‘Housing for All’ guidelines, Sale of free component can only be linked to the completion of the ‘slum rehabilitation’ component. Thus ensuring that rehabilitation projects are completed by private developers before they can benefit[2]. However housing activists blame this heavy dependence on private developers as the main reason for the sluggish performance with most private developers carrying out the construction in a very slow manner.

Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme

Under this scheme people falling under the Economically Weaker section (EWS) and Low Income Group (LIG) are eligible to seek loans from Banks and Housing Finance Companies with interest subsidy at the rate of 6.5 % for a tenure of 15 years. Manual Scavengers, Women (with overriding preference to widows), persons belonging to Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes/Other Backward Classes, Minorities, Persons with disabilities and Transgender are given preference under this scheme. Even after the subsidy, the EMI still proves to be high for the urban poor.[3]

Affordable Housing in Partnership

Under this vertical Mission seeks to provide financial assistance to Economically Weaker Section and Lower income groups houses being built with different partnerships by States/UTs/Cities. Central assistance is pegged at INR 1.5 lakh per EWS house. The construction by States/UTs/Cities is expected to be done in partnership with public/private sector. The central assistance however is too low to support construction of houses in metro cities like Chennai, Mumbai, Kolkata etc. Moreover, states may not even allocate fund for the construction of these houses and this to a large extent depends on the respective state’s welfare policy. Political differences between the state and the Centre also is an important factor for the implementation.

Beneficiary-led individual house construction

The final component of the mission seeks to provide assistance to EWS for the construction of a new house or for enhancement of an existing house. This component applies only to individuals and families who do not fall in any of the other components or redevelopment plans under the mission. Individuals under this component are eligible for a sanction of INR 1.5 lakh over 3-4 installments from the Central Government through the respective State Governments in order to construct or enhance the existing houses. The progress of these houses are to be tracked regularly by the authorities with the use of geo-tagged photographs.[4]

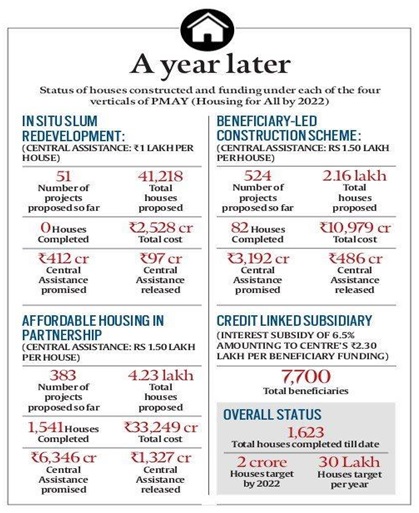

However, the amount is far too low for construction of houses in metro cities like Chennai, Mumbai etc. More than a year since its launch, PMAY which promises to construct 2 crore houses by 2022, at the rate of 30 lakh houses per year has merely sanctioned 3,58,703 houses and of which constructed only 20,801 houses in the Beneficiary Led Construction Scheme (BLCS),[5] and according to the State Wise Report on In-situ Slum Redevelopment (ISSR), a single house has not been completed of the 41,218 houses involved (as of 1st August 2016).[6] The success or failure of RAY is difficultto assess as it never really took off. In a nutshell, the progress and the performance of all these policies have been dismal contrary to the projections by the government. It begs the question; how can the executive be disciplined to deliver to their promises?

[1] http://mhupa.gov.in/writereaddata/Revised%20Guidelines%20BSUP%202009.pdf

[2] Under Section 4 of the Housing for all Guidelines

[3] 5.1- 5.12 of Housing For Guidelines

[4] 7.1- 7.8 of Housing For All Guidelines.

Add new comment