The people of Kodungaiyur, living under the shadow of mountains of waste, yearn for one thing - for the dumpyard that blights their neighbourhood to be gone. They have been promised this and more - a park where the dumpyard now stands is one of these promises. Generations have come and gone, but the dumpyard remains.

However, a recent burst of activity has been observed around it, filling the people with hope again. Under the Swach Bharath 2.0 scheme, the Tamil Nadu Government together with the Greater Chennai Corporation has signed contracts with three private agencies, with the aim of recovering resources and energy from the dumpyard, using the process of biomining.

- Zigma: A company specialising in biomining and managing legacy waste. They have other projects around Chennai, with the Pallikaranai Marsh Biomining management also in their portfolio.

- Ramky: A company specialising in solid waste, medical waste and hazardous waste management. This company was in a solid waste management contract with the Greater Chennai Corporation in 2012, which was then terminated on account of the poor performance of the company. The GCC also imposed a 6 crore fine on the company.

- Ascent: Originally an IT company, Ascent has also received a biomining contract.

Dumpyards are a blight on our landscape | CAG

What is biomining?

Dumpyards like Kodungaiyur have many decades worth of compacted solid waste. Elements like the sun and the rain breakdown these substances, resulting in the mixing of existing chemicals and the formation of new toxic substances. For example, when rain runs through the waste, it forms complex leachates which are a mix of several chemicals. These can go on to pollute the soil, underground aquifers and nearby water bodies. Similarly, decomposition of solid waste under the specific conditions created in dumpyards (heat, presence of other chemicals and solvents) creates gases, of which carbon-di-oxide and methane are the main components. Not only do these reduce the quality of air inhaled by residents, these also contribute greatly to climate change.

The aim of biomining is to break down these complex mountains of waste, segregate these and recover any material of worth from these (metals, paper, glass, fabric, glass etc). Materials that cannot be used for resource recovery, are utilised as fuel sources. An important aspect of biomining is also recovering compacted organic matter and returning their nutrients back into the soil.

There are some important steps to biomining:

- The first step is a feasibility assessment of the dumpyard through site investigation studies. The aim is to understand the chemicals in it and their properties, the surface area to be treated, wind direction and speed etc.

- This is followed by excavation. The waste obtained like this is piled in narrow rows called windrows. This is to facilitate the aerobic decomposition of organic matter in the waste, aided by periodically turning it over.

- This is followed by treatment with biocultures (or bio-inoculum) which hastens the decomposing process. This also reduces the volumetric weight of the waste (a process called stabilisation), bringing it down to more manageable levels.

- Further screening and segregation of waste happens at this stage through human intervention and the use of machines such as trommels, vibrating screens and air blowers. After resource recovery at this stage, waste that has no potential for recovery is sent off as alternate fuels to fire cement kilns, for use in construction, road laying etc. Waste that does not meet the criteria for even this (heterogenous waste), is sent to landfills for scientific disposal. Technically, these will remain as waste for the rest of their lives.

- The final step is levelling the dumpyard using machinery. This can be done once all the waste has been treated. It could be months or even years before a dumpyard is ready for this stage of treatment.

While the steps above are what are outlined as ‘bioremediation’ steps by the Central Pollution Control Board, these are by no means the only protocols followed. Biomining (or bioremediation) can involve several other steps and stages, depending on the nature of the dumpyard.

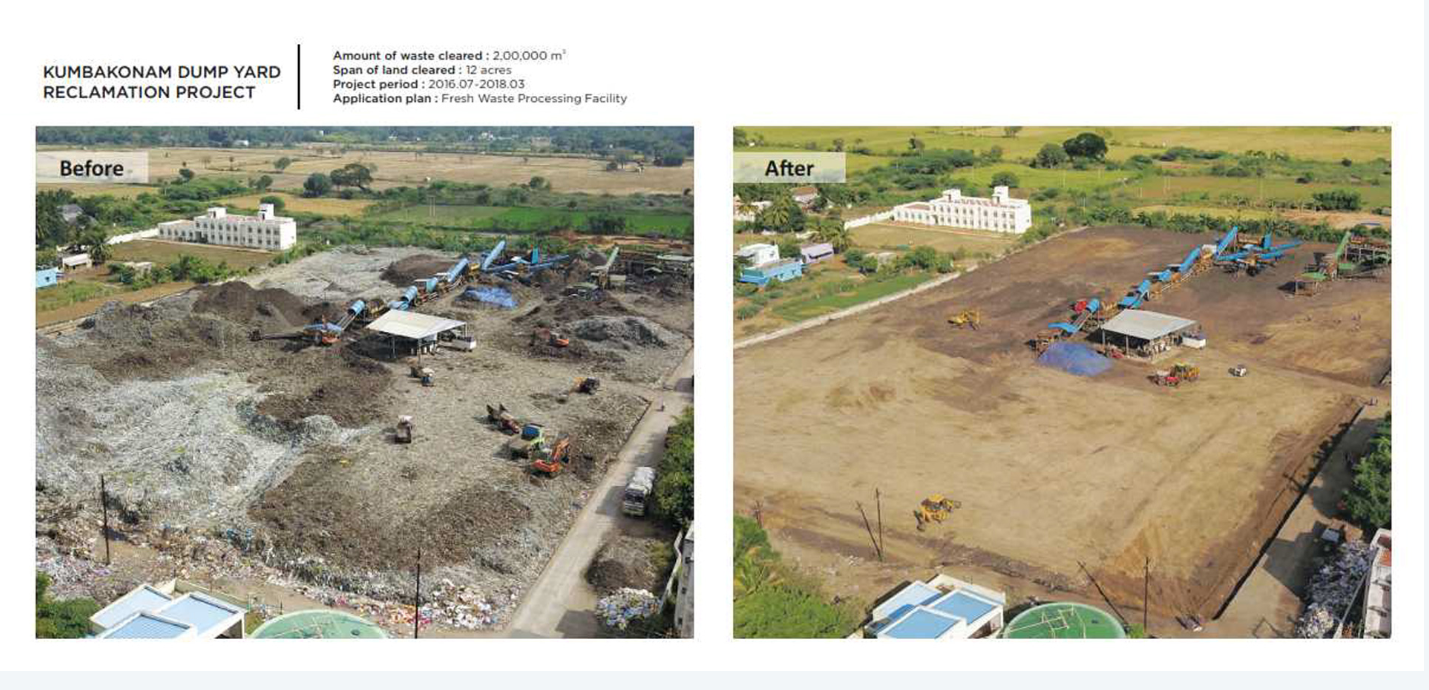

Pre and post biomining in Kumbakonam dumpyard | Zigma

The composition of waste and the limitations they impose

The Kondunigaiyur dumpyard has been functional for over 40 years now. Over the decades, the dumpyard has received an assortment of toxic waste including plastic waste, e-waste, medical waste, sanitary waste, industrial waste etc. Time, and the effects of weathering would have broken these materials down into microplastics, heavy metals and other toxic components. Even when organic matter is isolated from these dumpyards, it is likely to be contaminated with these pollutants. There is the risk therefore that fertilising fields with these is likely to contaminate the soil there, while introducing these toxic materials into our food chain. It is therefore important that dumpyard derived soil is analysed for toxicity. They should not be moved to other sites, if found to exceed preset toxicity thresholds. This needs to be mandated and monitored by the Pollution Board.

Equally importantly, households need to be taught the need to segregate at home. Without this basic behavioural change, the crores spent in bioremediation will be money down the drain. As we excavate, recover and recycle legacy waste at one end, new piles of unsegregated waste will be building up at the other.

Manufacturing companies must bear the biggest responsibility of all for the waste they create. Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) ranging from processed foods to cosmetics, and the waste they create, are packed into our dumpyards. Each contains unique toxic additives, the components of which are unknown to the consumer, and those offering remediation services. While the Extended Producer Responsibility laws address producer responsibility to an extent, it must also include their responsibility to declare the toxic additives in their products. And they must take up final responsibility for managing the end of life of these substances.

The people of North Chennai pay the price

Incinerators are another difficult to ignore elephant in the room. Burning waste in incinerators might seem a good way to make it disappear, right? The truth though is far from it. Incinerators produce toxic fumes and ashes. The fumes will once again enter people’s lungs, and the ash will mix into the soil and waterways, entering our food chain, and through this, our bodies. As for the people of Kodungaiyur, their respite from the polluted air and water caused by living next to a dumpyard will be short-lived. The incinerators will quickly take their place.

Just transition

Stakeholder consultation is an essential first step before any substantial change is introduced into people’s lives. Biomining and incineration are no exceptions to this principle. Neighbourhoods which are likely to be affected must be consulted through open, transparent processes that take into account their concerns and questions.

Equally important is the role of waste workers as stakeholders in waste management. For years now, the thankless job of managing Chennai’s waste and recovering components of value has been left to informal waste workers. Their toil over the years has now been rewarded by restrictions to entering dumpyard sites. Wouldn’t biomining have been a much more effective (and just) process if it had used the services and prior knowledge of these waste workers? That would have been ‘just transition’ - respecting their livelihoods and giving them the recognition they deserve.

Add new comment