Let’s take a moment to revisit our past, understand our present and look into our future. During my school days, until about 5th standard, my parents used to walk me to school. Gradually, my parents gained confidence in my traffic navigation abilities and let me cycle to school with a few friends from my neighbourhood. My normal routine after school involved playing in the local streets with my friends till dusk and getting back home when the street lights went on. After a certain age, I was independently mobile with the help of my cycle. I was free to venture into new territories with my friends and sometimes alone. And my parents never hesitated/ stopped me from cycling or walking alone to my school, tutoring class or the neighbourhood shop. At a very early age, I learned to navigate my locality and make short trips without any parental guidance. Those were the times when cell phones were not very popular among the public, so I was truly all on my own.

Today, I hardly see any children playing or cycling in my neighbourhood without parental supervision. Parents are paranoid at the thought of sending their children alone even for small errands within their neighbourhood. We cannot deny that just in the past decade, there has been a huge shift in children’s independent mobility. But why are parents so reluctant to send their children on their own? Have our cities become unsafe for kids? The answer is ‘yes’. Despite all our many advances, the poor design of our cities render vast tracts of them inaccessible to and/or unsafe for children. This has consequently led to a huge decline in independent mobility among children in our city - a trend that is also reflected worldwide. There are very few opportunities for children to go to parks or playgrounds without any parental supervision. Our society suffers from paranoia about leaving children on their own. In fact, India’s urban design is favourable to only grown men on motor vehicles leaving all the other marginalised groups disadvantaged.

Why focus on children’s independent mobility?

The ability to travel independently is vital to a child’s cognitive, physical, and social development. A study shows that by increasing independence, children are more likely to have a higher attention span and engage in activities whether it be educational or recreational. In addition, it helps to promote problem-solving which is a vital life skill. It also improves children’s social skills and increases their ability to interact in different settings. Independence for children with special needs opens up a world of opportunities for them, which our chaotic street design otherwise denies them. The most significant advantage is that independent travel builds perception and spatial relations, such as learning to navigate around obstacles, recognise footpaths, traffic lights, curbs, drop-off points, and respect personal space. Children who are exposed to limited mobility are considered to be at risk for secondary impairments such as cognitive, spatial perceptual and social-emotional delays.

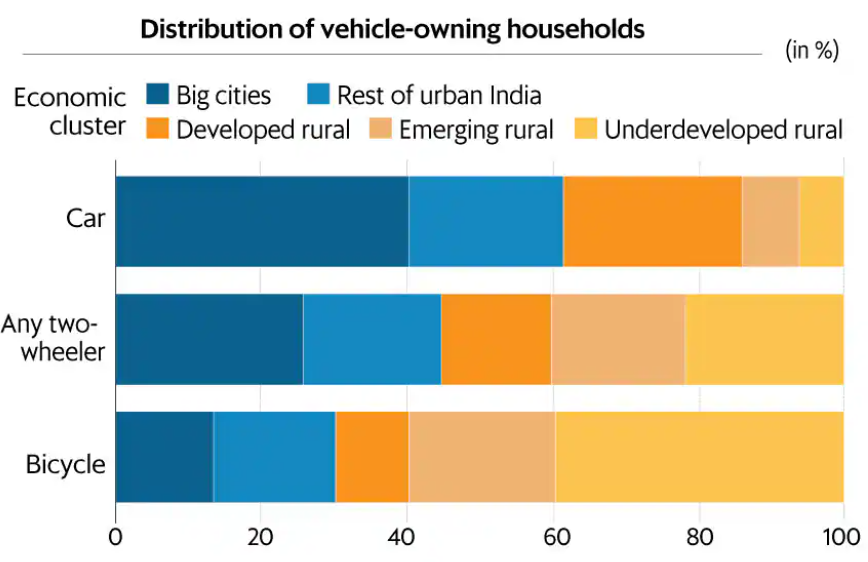

When we look at vehicle ownership, as per The National Family Health Survey, motorcycle ownership in Indian households has increased by 6 times (between 1992 and 2021) and car ownership has increased by 8 times (from 1992-2021). At the same time, bicycle ownership only increased by 1.1 times. The majority of this increase in motorised vehicles is seen in urban areas and bicycles are popular in emerging rural and underdeveloped rural areas. All this evidence points to increased motorisation of our roads, increased congestion, pollution, and fatalities.

Figure 1: Distribution of vehicle-owning households. Graph extracted from ICE 360°.

The result is that most parents in India prefer to take time off from their work to drop off/pick up their children from school. These are unnecessary trips that worsen traffic congestion, fuel costs, pollution and carbon emissions in the long run, creating a vicious cycle.

Is this about street design?

The physical, social, and economic characteristics of our cities directly influence the safety of our children. Poor pedestrian infrastructure, road accidents, lack of cycling infrastructure and an increase in motor vehicles on roads only create anxiety for both children and parents. Motorists not respecting pedestrian infrastructure like pedestrian crossings and footpaths, creates chaos. Such urban environments can compound insecurity related to safety.

Some of the other factors that influence parents are the neighbourhoods in which they live (metropolitan area, town or village), distance to school, the likelihood or perception of risks to safety and availability of vital infrastructure. Children from low-income families tend to have less access to structured sporting facilities but more access to free play in their neighbourhood. On the other hand children from middle and high group income have access to more structured facilities and chaperones most of the time. This limitation decreases the opportunity for children from middle/high-income families to experience independent mobility.

Individual and family characteristics can also permit or forbid commuting alone. For example, parents might have a general fear of strangers; or they might question their child’s competence to navigate a public space. Parents' education levels or their work patterns could also influence their willingness to send their children alone. Apart from these, social and community pressures, such as disapproval from family members and their social groups, might prevent parents from allowing their children to be sufficiently independent.

Gender is a key factor that can’t be ignored since even as an adult, gender determines travel patterns. Parents are less likely to send their daughters out alone than their sons at any age. Girls are generally more protected in an Indian family, and this impacts their opportunities for independence. An increase in reported incidents of crime against children and women in the past decades only makes it worse and disrupts independent mobility. All these factors put together negatively impact children’s independent mobility and restrict their freedom from a young age.

Therefore, while a host of factors determine how much independent mobility a family might allow its children, we also know that urban infrastructure is definitely one of those factors. Parents have seen cities change before their eyes - clogged with traffic, pollution and all manner of urban infrastructure that makes us dread travelling inside the city. They hear of macabre road accidents every day - each one preventable, had the right measures been set in place. Is it any surprise then that even those parents, who would have otherwise allowed their children a degree of independence, now refuse to? Those of us who are children from the 80s and 90s have lived through this change, and can clearly see why we have now ended up where we have.

So is there a way out? Yes. We have examples of cities that have successfully created child friendly spaces. These cities are already leading the way by centering children’s experience in their design with positive results to learn from. In Japan, for example, children (age 10) make as much as 85% of their trips around their neighbourhoods without their parents.

There is a Japanese proverb “Send the beloved child on a journey”. Allowing independence is considered the best way to show love! And how different it is to how our cities are set up. Japanese children attain independence and self-reliance at a very young age, as young as kindergarten. Japanese parents encourage their children to travel to and from school. Somehow Japanese cities have found a way to create safe urban spaces that are suitable for children. (Incidentally, Japan also has a very low crime rate which must add to parents’ peace of mind).

But in terms of independent mobility, there are lessons we can take from this island nation. There are simple measures that can be integrated into existing infrastructure to create child friendly urban spaces. For example, Japanese speed limits are low, and streets tend to have smaller blocks with a lot of intersections. This enables a safe environment for pedestrians to walk and not worry about speeding vehicles on the road.

Further, their transport policy is designed to prioritise public transport over motorised private transport. For example, they allow very few on-street parking spaces in their cities and no car parking on narrow streets. This ensures more visibility of the street to pedestrians. To discourage car purchasing in the city, residents have to prove that they have an off-street parking space to purchase a car. A design like this guarantees safe walkable neighbourhoods for children. A combination of a carefully designed urban space and underlying cultural value has created a quintessentially child friendly environment.

In India, one city has already begun correcting its mistakes and is striving to provide better infrastructure for their children. After witnessing several facilities of school children in the streets of Mumbai, the municipality took efforts to create safe, vibrant, walkable child-friendly streets. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai partnered with World Resources Institute and initiated trials to create safe school zones. They started by providing designated areas for walking and waiting areas outside school zones, including vibrant pedestrian crossings, pick up and drop off zones along with playful elements. As part of this trial, the school students were asked to state their commute patterns and the challenges they faced on the streets. Creating bulb-out extensions to footpaths provided more space to walk and reduced the distance required to cross the road. In addition, they also used various speed-calming measures to reduce vehicular speed in school zones.

As a result, they were able to increase compliance to stopping at pedestrian crossings to 41% (from 10% at regular pedestrian crossings). It was also noted that 93% of the schoolchildren felt that the streets were more accessible after the interventions. This is a great example of how well thought out changes in street design can significantly help to improve the safety of children. It is time other cities followed suit. Starting with school zones we can move up to bringing in changes at a neighbourhood level, in public transport and other public spaces.

Recommendations for Indian cities and towns to improve children’s independent mobility

- Create safe school zones with special design features for children; bring in stringent enforcement to penalise violations of these road safety measures.

- Encourage the use of sustainable modes of transport at a neighbourhood level, right up to a national level. By encouraging the entire population to shift to sustainable modes of transport we can increase walking, cycling and usage of public transport.

- Include children’s needs when designing public spaces and spatial planning of cities. For example, incorporate parks and playgrounds for children in all neighbourhoods at walkable distances.

- Create a national level policy and action plan to encourage and improve children’s independent mobility with the help of mass media.

- Invest in research and development to understand the mobility needs of children and develop knowledge of children’s independent mobility.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most significant change will be changing the behaviour and attitudes of parents when it comes to children’s mobility. But if we create small, safe spaces that parents can trust, we can progressively teach them to trust bigger spaces.

An independent child is a confident child; independence provides high self-reliance and freedom to express themselves. What a great way to create a future generation of citizens who understand and appreciate sustainable mobility! And let’s not forget the benefits of a healthier lifestyle that comes from a more active life - especially at a time when non-communicable diseases such as obesity and heart conditions are looming large in all our futures.

The last thing we want for our children is to feel left out, vulnerable and insecure in a social setting. By encouraging independence now we can help them to be stronger, more competent and capable of taking on the world and its challenges. As citizens and urban authorities, we need to strive to create a safe and clean environment, to enable children to flourish.

Add new comment