Every day, thousands of children in Chennai walk, cycle, or are dropped off on streets that were not designed with their safety in mind. While streets where schools are located are officially labelled as “school zones,” the ground reality is very different. Speeding vehicles, broken, encroached or no footpaths, unsafe crossings, and chaotic pick-up and drop-off practices expose children to serious road safety risks during their daily commute.

CAG’s road safety and sustainable mobility team undertook the Safe School Zones study to bridge this growing gap between how children travel to school and how streets around schools are currently designed and managed. The aim was simple but urgent: to make children visible in transport planning and to show that crashes near schools are preventable.

This urgency is backed by stark national and state-level evidence. In 2023, India recorded around 1.8 lakh road fatalities, with nearly 70% of these deaths caused by speeding alone. Speeding has now overtaken drunk driving, helmet or seatbelt non-use, and vehicle defects as the single biggest cause of road deaths. MoRTH (Road Accidents in India, 2023) reports that Tamil Nadu sits at the epicentre of this crisis, with the highest number of speed-related fatalities in the country with over 12,000 deaths due to speeding in a single year. Of these fatalities, 4557 were pedestrians, simply walking to their destination. For children, who have limited ability to judge speed and distance and are physically more vulnerable, this risk is even higher.

Along with the support of the city traffic police, we selected three schools from different parts of Chennai to capture the diversity of urban conditions and travel behaviour. These were:

- St. Gabriel’s Higher Secondary School (Don Bosco unit), Broadway – North Chennai

- Ramakrishna Mission School, T. Nagar – South Chennai

- Maharishi Vidya Mandir, Chetpet – Central Chennai

The schools differed widely in land use, traffic volumes, road user mix, and socio-economic backgrounds of students. This helped ensure the study reflected both common challenges and location-specific risks faced by children across the city.

The study examined school zone safety through three key lenses:

- Road infrastructure – footpaths, crossings, signage, visibility, and street layout

- Road user behaviour – vehicle speeds, parking patterns, pedestrian movement, and conflicts

- Parents’ perceptions of safety – how safe they felt allowing children to walk or cycle

A mix of road safety audits, mapping exercises, observational surveys, and stakeholder discussions were used to build a holistic, on-ground understanding of risks outside school gates.

Our Findings:

Speeding was the main point of concern identified by parents in our perception survey. Vehicles often moved at unsafe speeds even during school start and end times, despite schools being designated as sensitive zones. Scientific evidence clearly shows why speeding matters: every 1 km/h reduction in average speed can reduce the risk of a fatal crash by 3–4%. At 30 km/h, a pedestrian’s risk of death is about 10%, but at 70 km/h, it exceeds 90%. Yet, streets around schools frequently allow speeds far beyond what is survivable for a child.

The study also found that footpaths were either missing, broken, or encroached upon, forcing children to walk on the carriageway. Safe pedestrian crossings were poorly marked or absent, visibility was compromised by parked vehicles and vendors, and there were no clearly defined waiting or gathering spaces for children. Pick-up and drop-off zones were unmanaged, leading to sudden stops, wrong-side parking, and dangerous interactions between vehicles and children.

Photo: Vendors encroaching footpaths near Don Bosco School, Broadway

Photo: Footpaths on Burkit road with various types of encroachments near Ramakrishna Mission School, T.Nagar.

Photo: Illegal parking near Ramakrishna Mission School, T.Nagar.

Importantly, while policies and court directives for school safety exist, implementation was inconsistent and fragmented. Responsibility was split across multiple agencies, with limited coordination between traffic police, local bodies, and schools themselves.

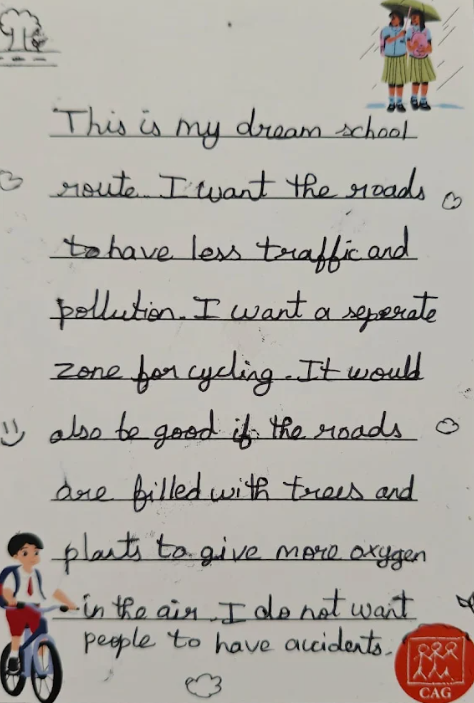

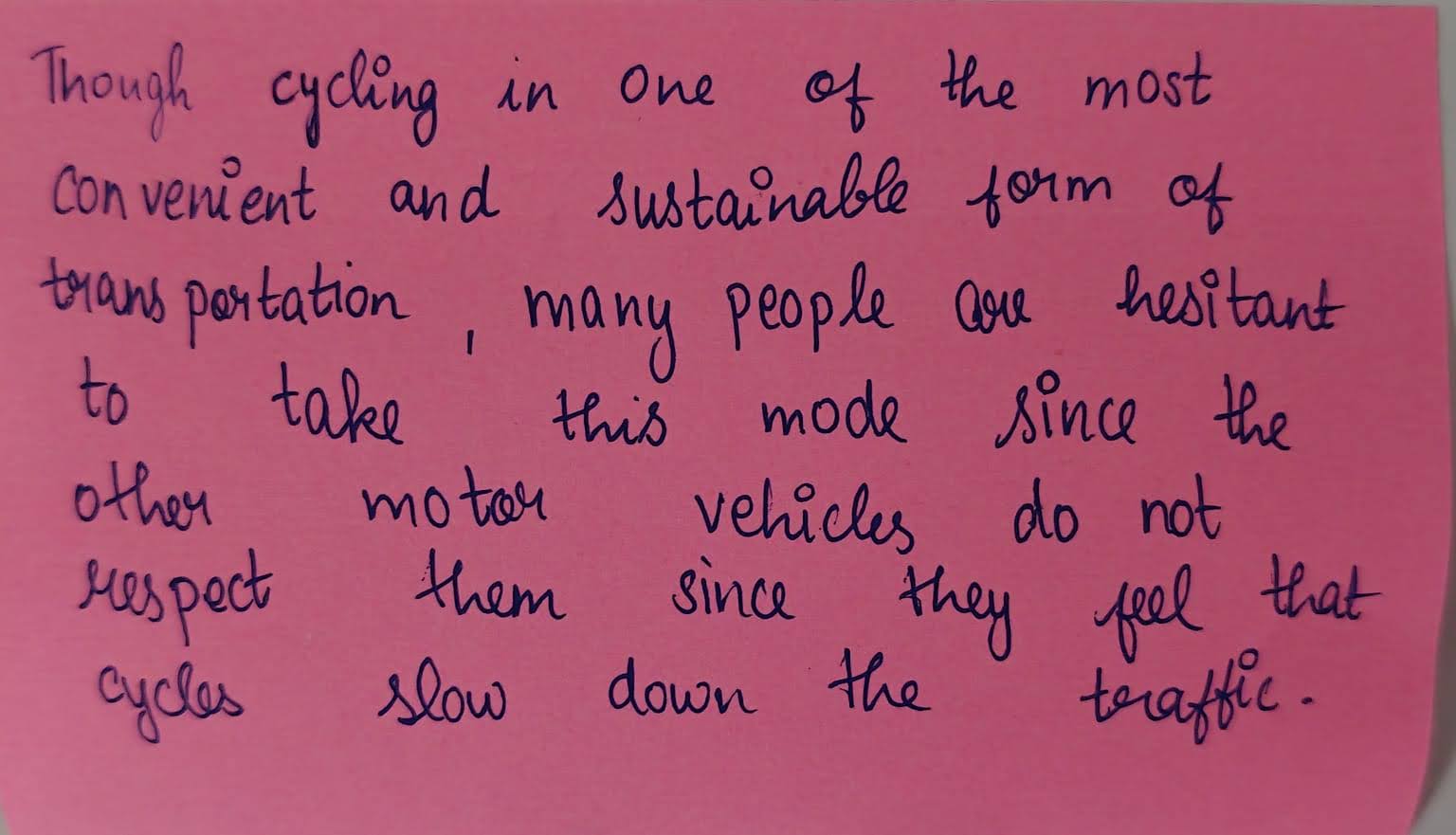

Students speak up

We felt it was important to hear from children about what they think and with this in mind we visited schools across Chennai to ask children how they imagine their dream school route. We found that even when children lived within a kilometre of school, they were not allowed to cycle to school due to safety concerns. The children who did cycle to school reported feeling nervous when vehicles passed too close to them. They reported feeling ill from traffic exhaust, experiencing headaches by the time they even reached school and said that they would love to see wide un-encroached pavements for them to walk along, segregated cycle paths and less traffic congestion on their way to school.

Photo: Students' letters about their dream school routes.

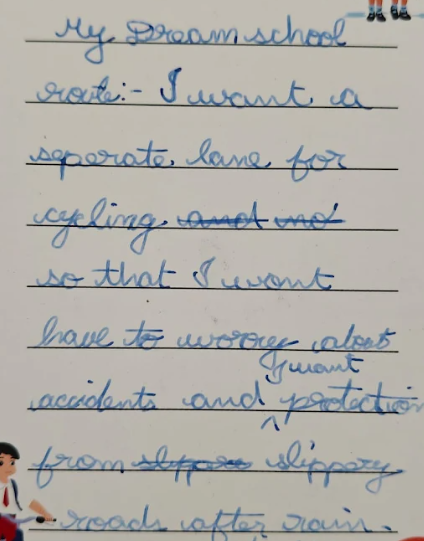

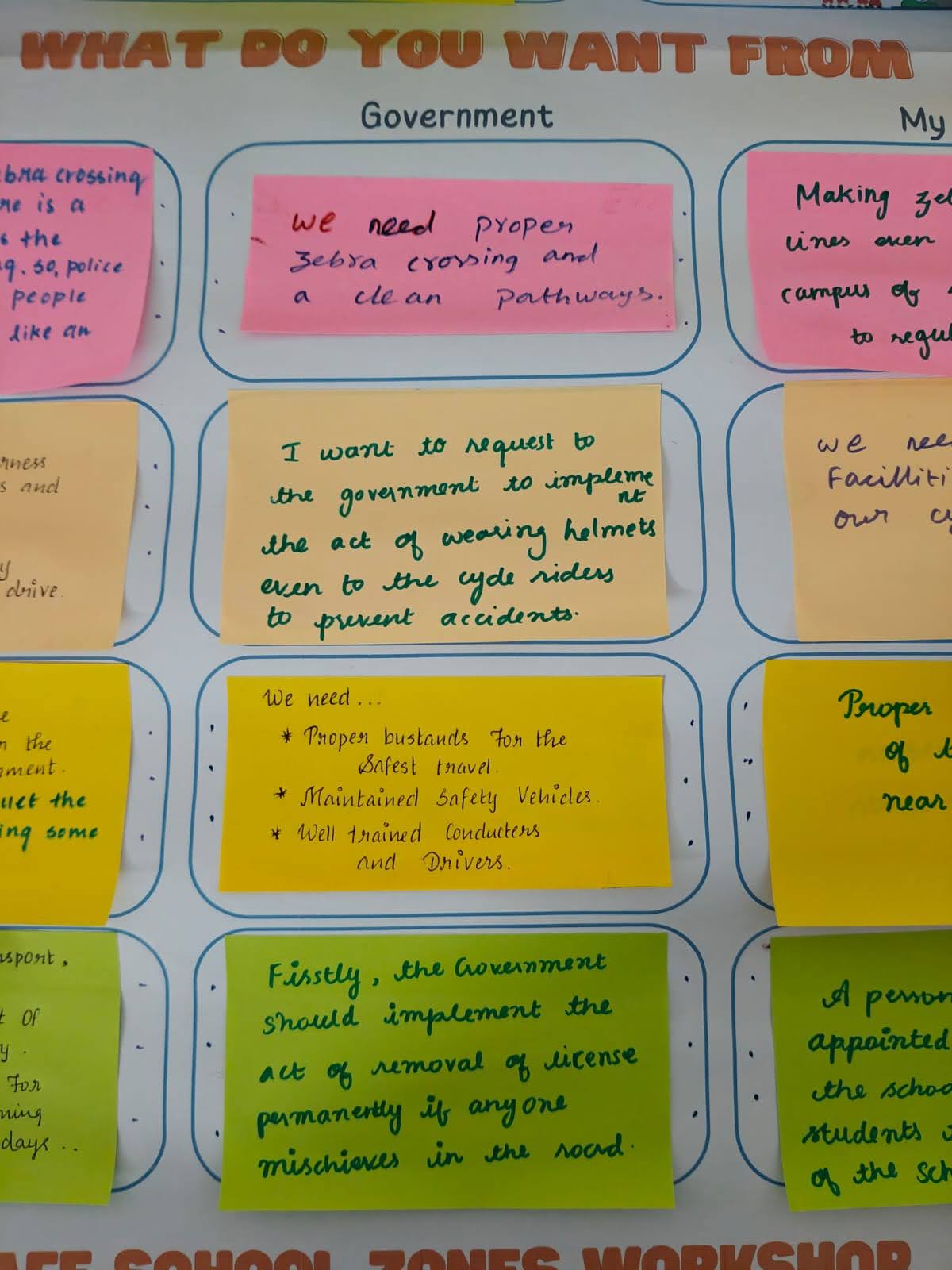

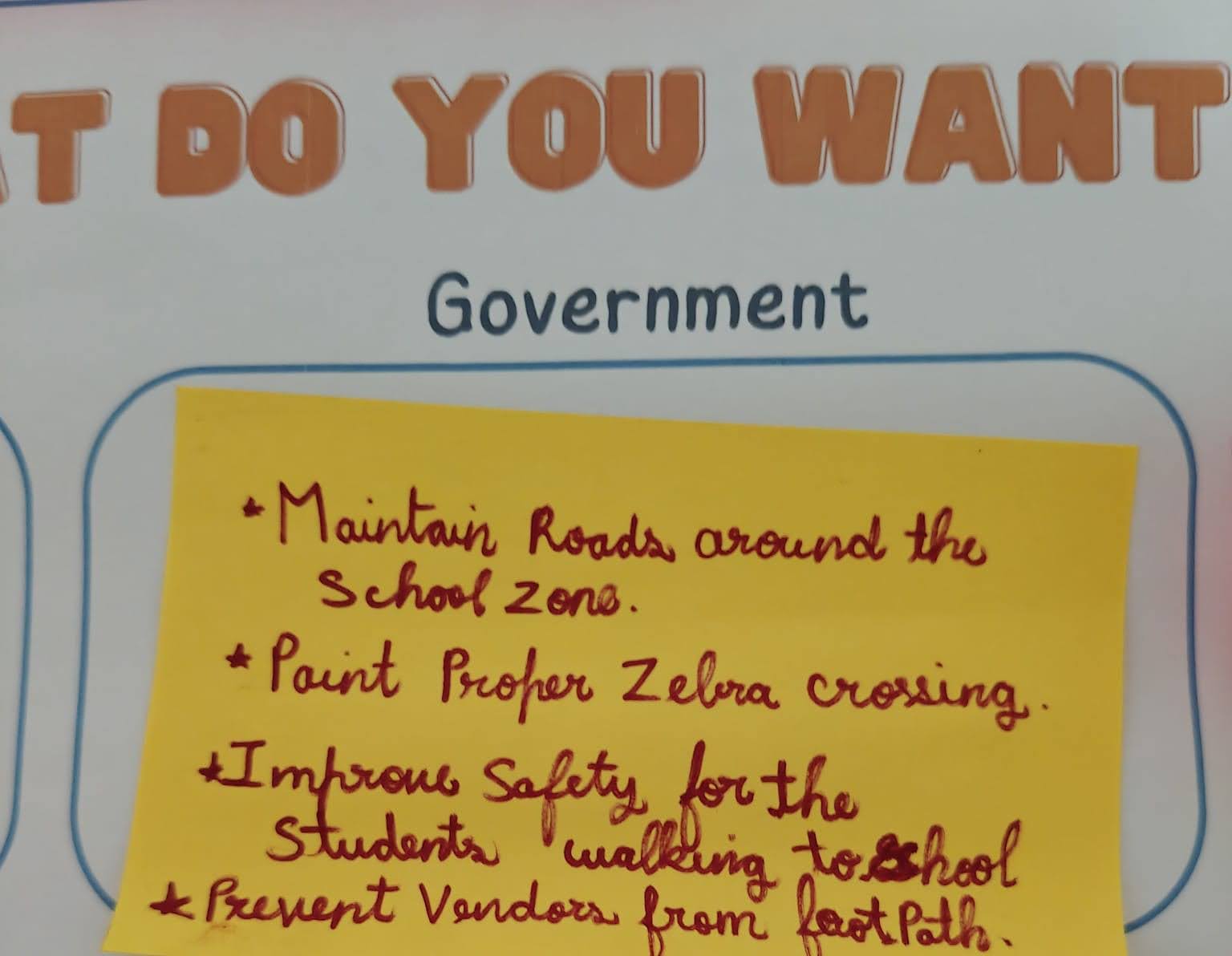

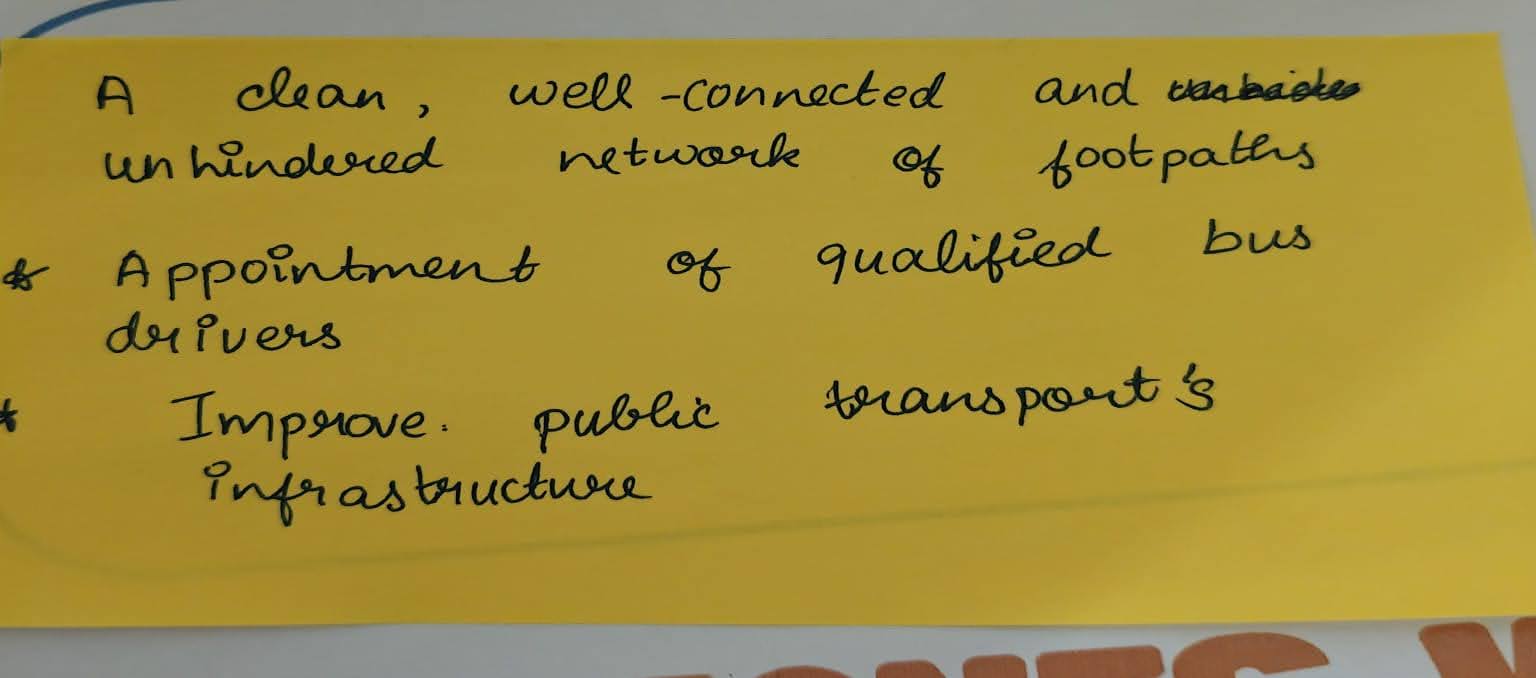

This was an important exercise as not having safe access to streets means that children grow up not knowing their city – an important element in feeling a sense of ownership and belonging. A lack of infrastructure and safe routes to schools also means that childhood joys of cycling or walking to school that also teaches independence and responsibility are taken away from children. In another workshop, we asked students to put down their suggestions on what could be done to address the issue of safer routes to schools. It became clear that children, who are the most important stakeholders of this study, understand and think about this issue deeply.

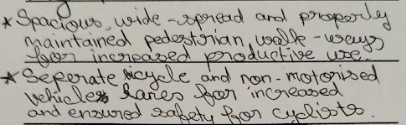

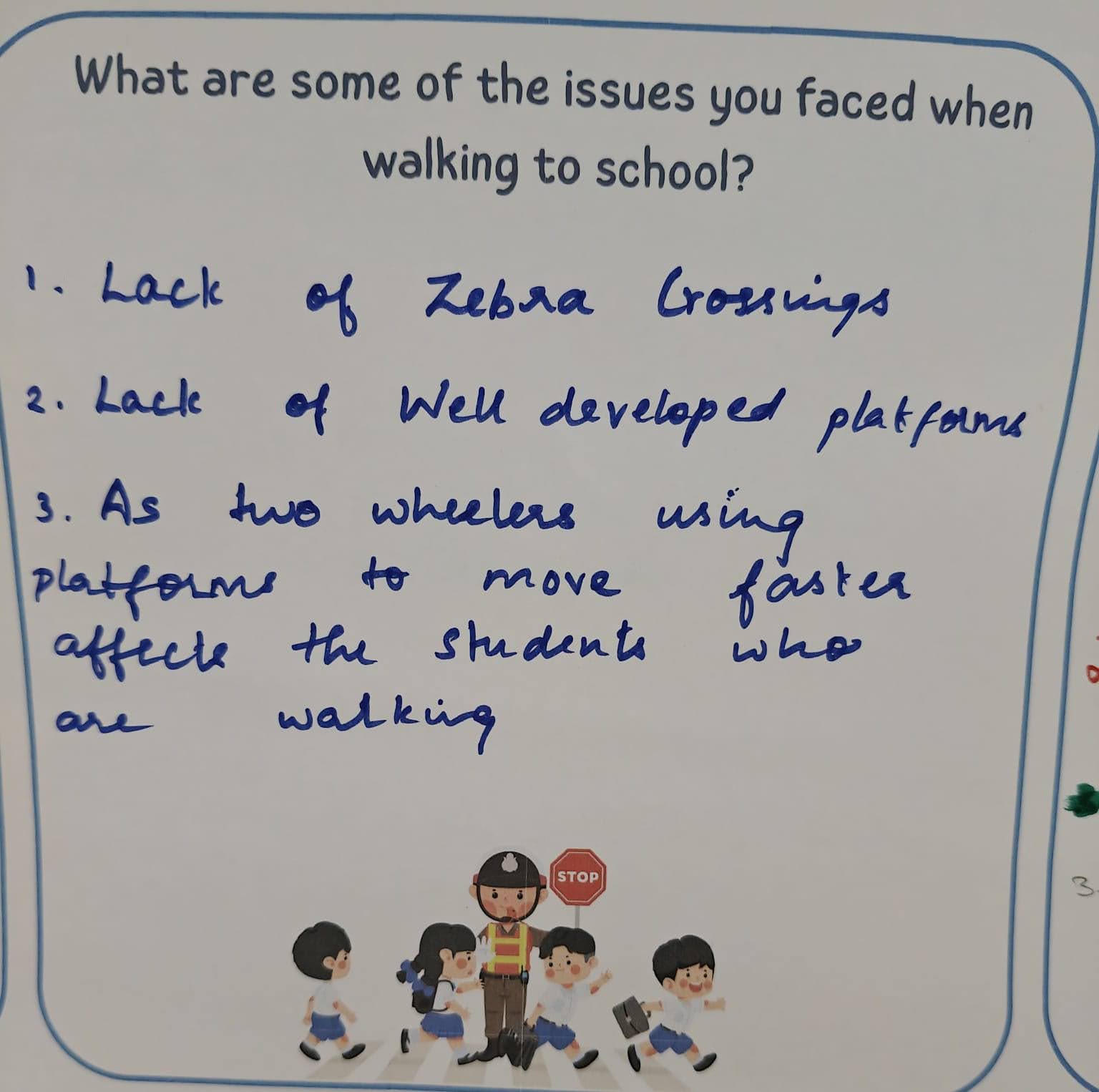

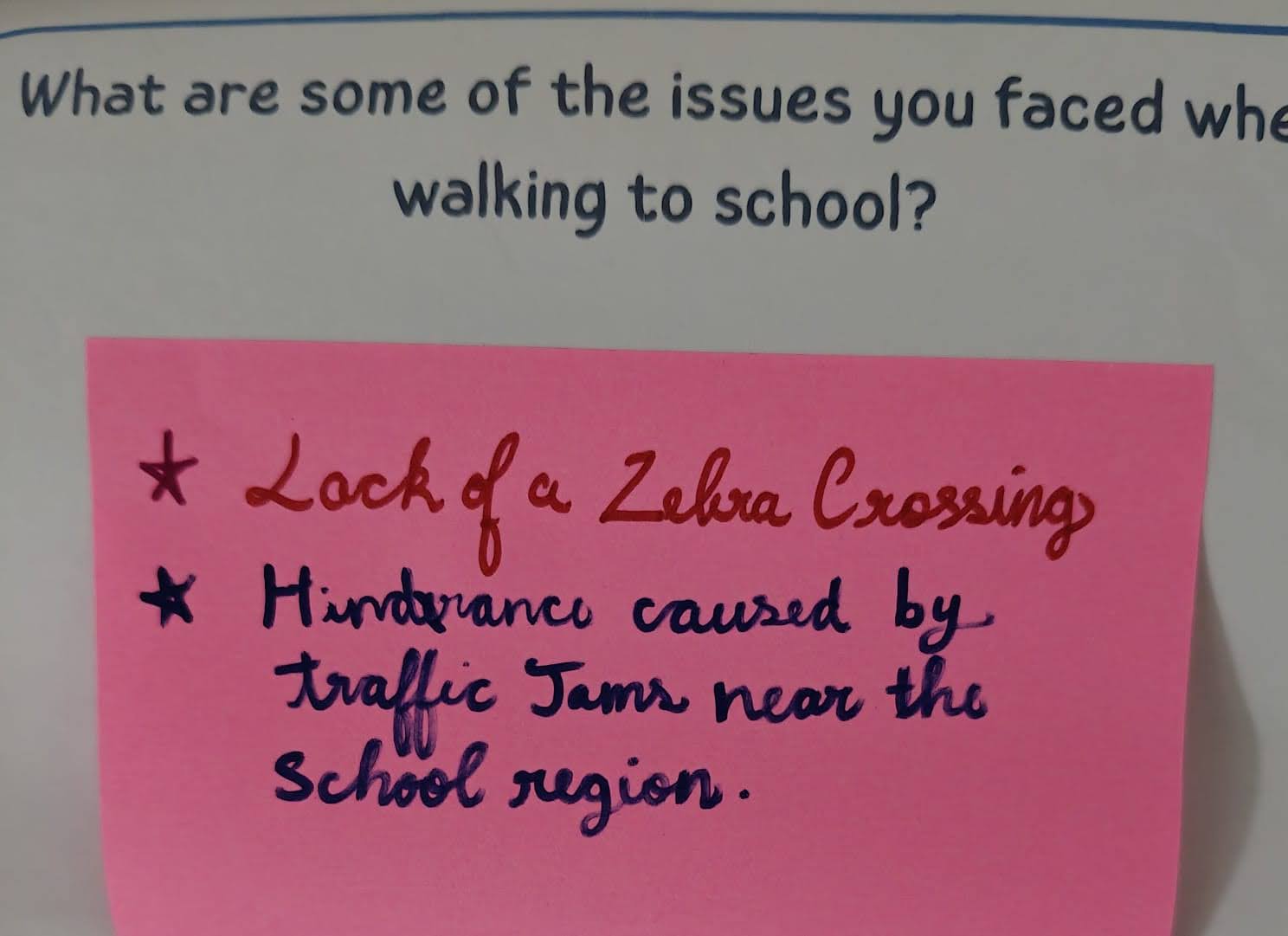

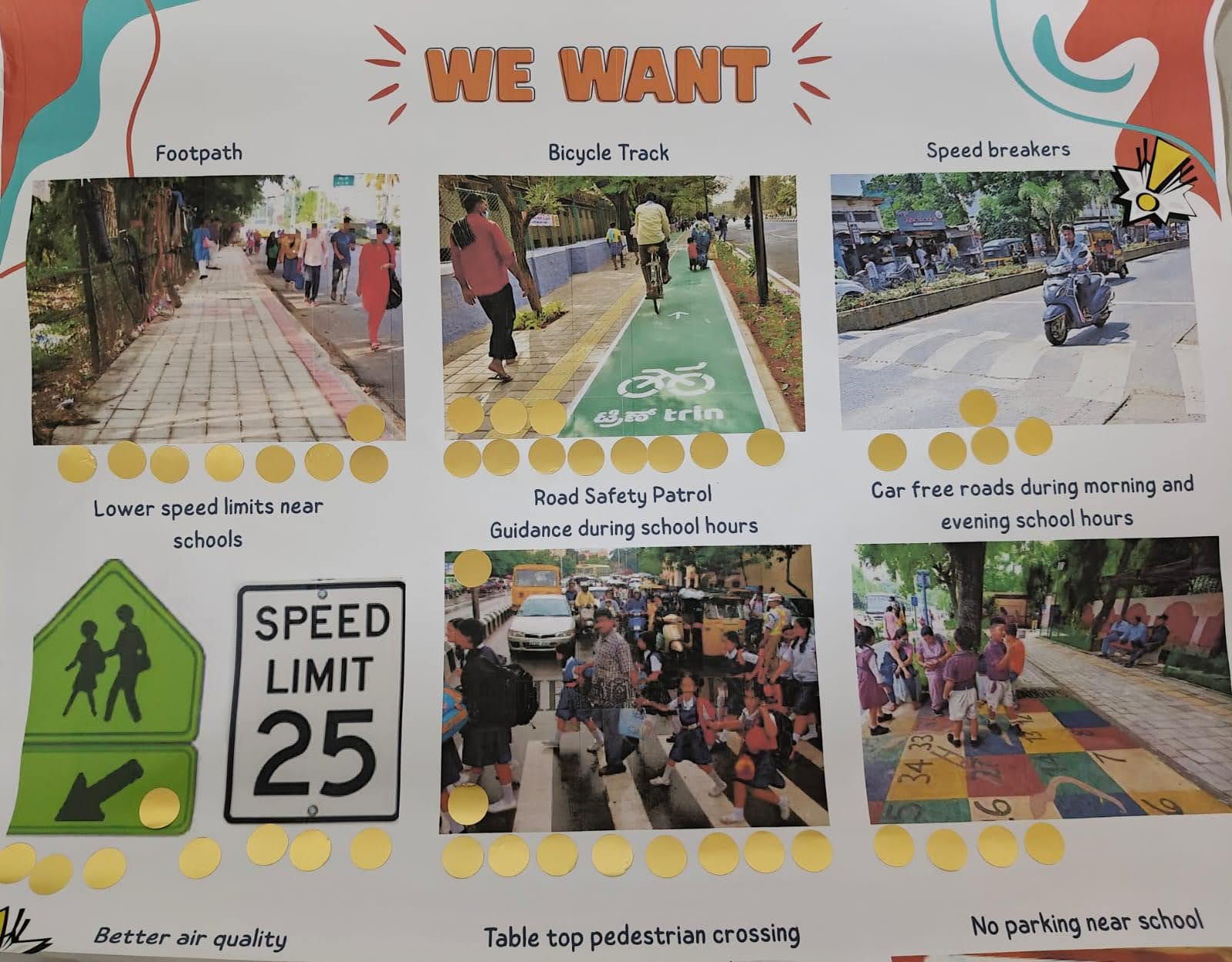

The students in our workshop said that the most common problems they face going to school and back is the lack of pavements that are safe, continuous and unobstructed. They also spoke about feeling unsafe while cycling and wanted segregated cycle paths. Many students pointed out the lack of very basic infrastructure such as zebra crossings. The following images are from the workshop sheets.

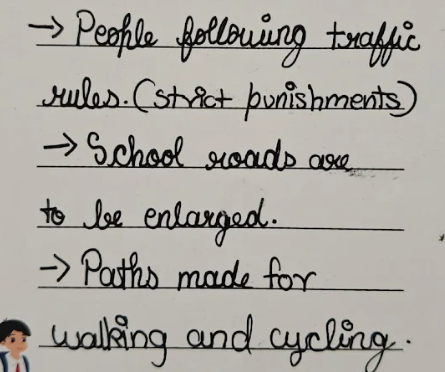

We also asked students what they expect from the traffic police and the government to address these issues. Again a lack of basic amenities were pointed out. The bottom line is that children feel unsafe on their school routes and this must be addressed urgently. Here are some images of what students expect from the authorities.

Photo: Students are casting their votes on the essential public infrastructure improvements needed near their schools to enhance their daily commute.

Finally we asked students to vote on what they considered the most urgent issues on their school routes. Bicycle tracks, footpaths and lower speed limits in school zones scored high. Students also wanted a road safety club member or traffic official to man zebra crossings and ensure their safety.

Pic: Students vote on issues they consider most urgent

What the Study Means

The Safe School Zones study shifts the conversation from blaming individual road users to questioning how streets are designed. Road safety cannot rely on enforcement and awareness alone, especially around schools. Streets must be designed to be self-enforcing and forgiving of mistakes, through measures such as traffic calming, safe crossings, clear signage, and consistent school-zone treatments.

The study also highlights children as a distinct category of vulnerable road users whose needs must be prioritised in street design. When streets feel unsafe, parents are pushed towards private vehicles, increasing congestion and risk for everyone. One major impact of traffic congestion is air pollution, an issue that is not taken very seriously although it has critical and lasting impacts on health and wellbeing.

Safer school zones, therefore, are not just about protecting children. They support sustainable mobility, public health, and healthier cities.

The following are the recommendations from the study:

Continuous, obstruction-free pedestrian paths

- Provide a uniform, wide, continuous footpath or paved shoulder near schools.

- Remove encroachments, vendors, transformers, or parked vehicles blocking pedestrian movement.

- Add street furniture or bollards/guardrails to prevent re-encroachment and protect walkers.

Safe road crossings for children

- Install zebra crossings/tabletop crossings directly in front of school gates and nearby junctions.

- Provide rumble strips before crossings to slow approaching vehicles.

- Deploy crossing guards and traffic police, particularly during peak hours.

- Encourage Student Road Safety Patrol involvement.

Speed management and visibility of school zones

- Enforce a 25 kmph speed limit in school zones.

- Install flashing beacons and speed limit signboards.

- Repaint speed breakers and lane markings for visibility.

- Add vibrant school zone road markings and wall painting to alert drivers.

Parking and traffic regulation

- Enforce strict no-parking near school gates and regulate on-street parking.

- Use zig-zag markings or camera enforcement (ANPR) to prevent illegal parking.

- Restrict loading/unloading and heavy vehicle movement during school hours.

- Provide clear centerline or vibration markings to organise traffic flow.

- Prevent unsafe U-turns with barricades or lane separators where required.

Organised pick-up and drop-off systems

- Create designated pick-up/drop-off zones either inside school premises or along the road shoulder.

- Stagger arrival times to reduce congestion during peak hours.

- Provide personnel to guide auto-rickshaws and two-wheelers during entry and exit.

Provision for cycling and walk-to-school safety

- Pave and mark shoulders for walking and cycling wherever feasible.

- Introduce cycle lanes using raised or differently paved surfaces to deter parking.

Bus stop and junction safety

- Redesign bus stops/shelters to avoid conflicts with pedestrians.

- Improve junction control using barricades or signals where turning conflicts occur.

The report and recommendations were handed over to the GCTP who assured us that they would include the school zones we audited in the 25 school zones they are planning to make safer.

By documenting real, everyday risks and converting them into measurable evidence, the study provides a strong foundation for evidence-based advocacy. It shows that crashes near schools are preventable and that relatively low-cost, design-led interventions can save lives. Most importantly, it makes a clear case for placing children at the centre of transport planning, where they belong.

The full report from the study can be read here.

---

Add new comment