For much of human history, the natural environment was an ever-present force shaping daily life. People lived in close connection with its rhythms and patterns, adapting to seasonal cycles and the landscapes around them. Over time, industrialisation and urbanisation transformed these organic systems into human-made environments, from compact villages to sprawling cities. Today, for many, nature is no longer experienced in its wild form but as curated fragments within the built environment. This constructed world has become our primary interface with the climate, shaping not only how we experience it but also how we alter it. The ways we build, inhabit, and consume have compounded over decades, intensifying climate change and transforming it from a scientific concern into a global and societal challenge.

Once discussed mainly within scientific circles, it now shapes headlines, policies, and public debate. Yet, for many, it remains distant and abstract, communicated largely through statistics, projections, and models that are difficult to relate.

In the current context, most people relate to climate through their built surroundings. This mediated setting not only shapes but also constrains our understanding of climate. The very activities that sustain urban life contribute to rising temperatures, sudden shifts in precipitation, and intensifying storm patterns that further influence how we perceive climate change. Because our experience is filtered more through constructed spaces than through direct interaction with natural systems, our perceptions are often partial and limited. This distance underscores the importance of effective climate communication not only to translate scientific terms or data into relatable narratives but also to help people reconnect with the realities of a changing world.

It is in this space that the Citizen consumer and civic Action Group (CAG) positions its work. With a firmly people-centric approach, rooted in decades of advancing environmental justice and amplifying citizen voices in decision-making, CAG has expanded its focus to climate communication. Recognising that addressing climate change requires not only scientific accuracy but also public resonance, CAG seeks to bridge the divide between technical framings of climate risks and the everyday realities of communities.

To take this forward, CAG has initiated efforts to make climate communication more accessible and meaningful in everyday contexts. These include developing a Climate Change Communication Toolkit with the Government of Tamil Nadu to simplify complex concepts for decision-makers and communities; working with educators to integrate climate communication into school textbooks, fostering climate literacy from an early age; and promoting decentralised renewable energy (DRE) solutions that highlight practical benefits for households, agriculture, and small industries. Together, these initiatives reflect a shift towards embedding climate awareness across governance, education, and community practices, supporting informed choices and sustainable futures.

This article builds on these efforts by exploring how climate communication can also be embedded within the built environment, using design narratives as powerful tools to make climate action tangible, local, and motivating for collective action.

The need to localise climate communication

Climate messages are often complex because they’re technical, impersonal, and disconnected from people’s daily lives. Terms like “net zero” feel intangible and confusing, making it hard for people to relate them to their everyday experiences. With limited funding, few large-scale campaigns, and minimal engagement, climate communication struggles to resonate. Making messages simple, relatable, and locally relevant is key to sparking understanding and action.

Scientific projections warn of various climate-related events, many of which are already changing how we live, work, and build. The built environment, including homes, infrastructure, public spaces, and cities, is both a major cause of and vulnerable to climate change. Problems like urban heat islands, poor drainage, and energy-heavy construction increase risks, especially for marginalised communities. At the same time, thoughtful design and management of these spaces offer powerful opportunities to cut emissions, adapt to new challenges, and strengthen resilience.

For this potential to be realised, climate communication must connect global science to local realities. People need to understand what climate change means for their streets, homes, and neighbourhoods, and what they can do in response. Limited access to timely, data-backed information often restricts alignment between policymakers and communities, underscoring the need for inclusive, locally grounded approaches. Communication that is culturally relevant and narrative-driven, drawing on local stories, traditional knowledge, and familiar examples, can make climate impacts more relatable and motivate meaningful action.

The Role of Narratives in Shaping Climate Communications

A narrative is more than a story; it is a way of connecting facts, context, values, and vision into a coherent whole. In climate communication, narratives help people not only grasp the challenge but also see their place in shaping solutions. By weaving together scientific evidence with lived experiences and collective aspirations, they make complex issues more immediate and actionable.

Strong narratives extend beyond environmental impacts to reflect everyday concerns such as health, safety, livelihoods, cultural identity, and community well-being. When grounded in local values and traditions, they resonate deeply. For example, in Kerala, local stories of shifting monsoon patterns help farmers understand how climate change affects crop cycles and guide adaptation strategies like adjusting planting schedules. In coastal fishing communities, traditional knowledge about tides and seasonal fishing patterns informs early warning and evacuation planning during cyclones. In urban areas, narratives around the cultural significance of trees and community gardens have been used to promote green spaces that cool neighbourhoods and improve health.

By grounding scientific facts in local context, effective narratives guide communities toward practical actions, build resilience, and encourage cooperation between citizens, authorities, and institutions in addressing climate challenges.

Built Environment as a Medium for Narratives:

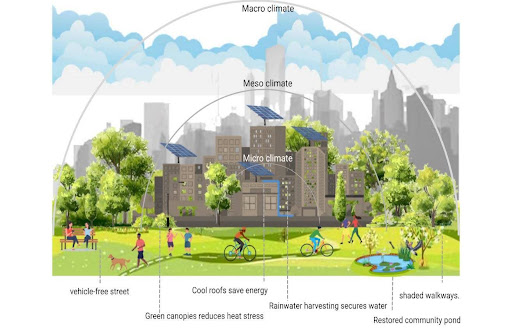

The built environment is both a cause of and vulnerable to climate change. It accounts for a significant share of global emissions, yet it is also where the impacts of heat, flooding, and resource stress are most directly felt. This makes it an ideal medium for climate communication. Figure 1 illustrates how climate communication can be grounded in design narratives that connect everyday urban experiences to broader climate systems. It shows the interplay of macro, meso, and micro climates, while highlighting tangible interventions like vehicle-free streets, shaded walkways, green canopies, cool roofs, rainwater harvesting, and restored ponds that people can easily relate to. By translating abstract climate concepts into visible and relatable design elements, the narrative makes the idea of resilience and adaptation more accessible, showing how collective choices in our surroundings directly shape comfort, sustainability, and responses to climate change.

Figure 1: Narratives of Climate in the Built Environment | CAG

Climate narratives in the built environment can operate at different scales:

- Micro-climate (Building scale): Local conditions around a building such as temperature, humidity, and wind are shaped by design choices. Features like shaded courtyards, cool roofs, and green walls not only reduce heat but also serve as visible examples of climate adaptation. With the help of signage or interactive displays, these elements can explain their benefits, turning everyday structures into ongoing lessons on sustainability.

A good example is the IIT Madras campus, where energy-efficient designs like ventilated roofs, shaded walkways, and natural landscaping help lower indoor temperatures and cut energy use. By incorporating these features into daily spaces such as classrooms, hostels, and pathways, the campus offers students and staff relatable, real-world demonstrations of climate-friendly practices. Informational boards and workshops further enhance understanding, making climate adaptation approachable and actionable (GRIHA). This way, the building itself becomes a tool for learning, showing how sustainable choices can seamlessly become part of everyday life.

- Meso-climate (Neighbourhood scale): Urban features like street orientation, green cover, water bodies, and open spaces influence how neighbourhoods experience climate. Tree-lined streets help reduce urban heat, while restored ponds and wetlands can prevent flooding during heavy rains. Community events, workshops, or public art installations that explain these benefits help residents connect everyday spaces with climate resilience.

For example, after the severe flooding in 2015, several residential areas in Chennai implemented rainwater harvesting, restored ponds, and promoted community-led waste management. Public campaigns and awareness drives clearly explained how simple actions like cleaning ponds or planting trees can reduce flood risks and lower heat stress (ADB). These communication efforts have made a tangible impact: more residents are actively participating in climate adaptation measures, local water bodies are being maintained, and community engagement has strengthened. By using relatable examples and encouraging collective action, effective climate communication is transforming how neighbourhoods respond to climate challenges, building resilience from the ground up.

- Macro-climate (City scale): Cities operate at the regional scale and are shaped by broader climatic systems such as monsoons, seasonal winds, and drought patterns. At this scale, populations and communities are highly diverse and heterogeneous, with varying beliefs, values, levels of trust, and information preferences. As cities grow and become more complex, climate communication strategies need to be tailored to resonate with this wide array of users. Research on audience behaviour can guide the design of messages to ensure they are clear, relevant, and actionable for different groups.

Coimbatore’s city-level planning serves as an effective communication channel in this context. Initiatives such as expanding green cover, improving water management, developing sustainable mobility networks, and restoring lakes not only enhance urban resilience but also act as indirect, tangible demonstrations of climate action (ICLEI). Unlike direct communication methods—such as informational boards or pamphlets which may have limited reach or impact, these visible infrastructure changes communicate climate risks and solutions through lived experience, everyday observation, and community interaction. Public workshops, media campaigns, and interactive platforms further amplify this effect, co-creating understanding among stakeholders and establishing shared norms. By linking observable urban changes to residents’ daily lives, city-level planning becomes a dynamic medium for climate communication, engaging diverse audiences and motivating meaningful, collective action.

By framing these scales through stories that people can see, feel, and participate in, climate communication moves from abstraction to lived experience.

Conclusion:

Facts alone rarely inspire change. Narratives rooted in local realities and embedded in the built environment can turn climate awareness into climate action. They give context to impacts, connect people emotionally to the challenge, and frame solutions in ways that are tangible and relevant.

As the saying goes, “People will forget what you said, but they will never forget how you made them feel.” In climate communication, that feeling can be the spark that transforms passive awareness into active commitment. By weaving compelling narratives into the spaces where we live, work, and gather, climate change becomes not a distant concern but a shared responsibility and an opportunity to shape a resilient, equitable future.

Add new comment